A Conservation Army Mobilizes

Given its quiet beauty today, it’s hard to believe that South Mountain Park played host to some 4,000 members of a peacetime conservation army between 1933 and 1940, but that is the fact of the matter. Indeed, without this peaceful occupation by self-proclaimed “Soil Soldiers,” Phoenix South Mountain Park would not exist as we know it today.

When Franklin Roosevelt assumed the office of president in 1933, America was in its fourth year of what has come to be called The Great Depression. Fully one-quarter of the population was without work and some 2 million young men and women are believed to have taken to the road in search of work and a meaningful future. Rightly or wrongly, many grew fearful that this wandering generation would fall into mischief or worse, under the spell of agitators. Action was needed and fast.

Among the many programs created in the first 100 days of Roosevelt’s fledgling New Deal was the Emergency Conservation Work program, which came to be known as the Civilian Conservation Corps – the C.C.C. Open to young, single men aged 17 to 28, the C.C.C. mobilized over 250,000 enrollees in the spring of 1933 and by the time the program was discontinued following the attack on Pearl Harbor, some 3 million young men served in the program, working in camps in every state and territory of the United States. Arizona saw its share of benefit from the labor of the C.C.C. On average 50 camps operated in the state and by 1942 some 41, 362 Arizona men received valuable employment and training in the C.C.C.

Given its quiet beauty today, it’s hard to believe that South Mountain Park played host to some 4,000 members of a peacetime conservation army between 1933 and 1940, but that is the fact of the matter. Indeed, without this peaceful occupation by self-proclaimed “Soil Soldiers,” Phoenix South Mountain Park would not exist as we know it today.

When Franklin Roosevelt assumed the office of president in 1933, America was in its fourth year of what has come to be called The Great Depression. Fully one-quarter of the population was without work and some 2 million young men and women are believed to have taken to the road in search of work and a meaningful future. Rightly or wrongly, many grew fearful that this wandering generation would fall into mischief or worse, under the spell of agitators. Action was needed and fast.

Among the many programs created in the first 100 days of Roosevelt’s fledgling New Deal was the Emergency Conservation Work program, which came to be known as the Civilian Conservation Corps – the C.C.C. Open to young, single men aged 17 to 28, the C.C.C. mobilized over 250,000 enrollees in the spring of 1933 and by the time the program was discontinued following the attack on Pearl Harbor, some 3 million young men served in the program, working in camps in every state and territory of the United States. Arizona saw its share of benefit from the labor of the C.C.C. On average 50 camps operated in the state and by 1942 some 41, 362 Arizona men received valuable employment and training in the C.C.C.

The Camp That Almost Wasn’t

South Mountain was a likely candidate for placement of a C.C.C. camp when the second phase of work began in the fall of 1933. Little had been done to improve what was then known as Phoenix Mountain Park following its creation in the 1920s so the area seemed a natural fit for the establishment of a C.C.C. camp to perform useful work and create valuable improvements. Nevertheless, there was a snag. The government mandated that C.C.C. camps must possess a source of potable water. In 1933, Phoenix Mountain Park lay some 8 miles outside the Phoenix city limits and possessed no viable source of water.

The city balked at the idea of providing a water supply for the then remote park site so Phoenix’s application for a C.C.C. camp was denied. There the matter might have rested if not for the intervention of Senator Carl Hayden who contacted the Office of National Parks, Buildings and Reservations to assure them that the $5,100 needed to provide a water supply would be taken care of. Senator Hayden was able to impress upon city officials the important potential benefits of having a C.C.C. camp at the park and on October 25, 1933, the Arizona Republic proclaimed “Opening of Mountain Park Well Assures Corps Camp.”

The Showplace Camps

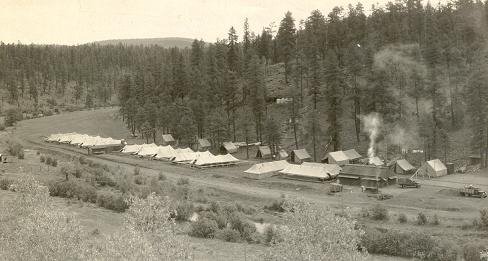

Senator Hayden’s efforts paid out in spades because South Mountain was actually allotted two C.C.C. camps, designated SP-3-A and SP-4-A. The establishment of two camps so close to Phoenix can be traced to a request from the Secretary of the Interior to the director of the C.C.C. asking that some camps be established in areas adjacent to population centers. The proximity to a major city meant that the South Mountain Park C.C.C. camps became the showpiece camps of the Phoenix District, with civic leaders and dignitaries dropping by seemingly without notice.

Louis Purvis, an enrollee who transferred to South Mountain with the rest of his C.C.C company from a camp at Grand Canyon in October 1937, described camp SP-3-A in his book, The Ace In The Hole:

The road from Phoenix to South Mountain came through the campsite, separating the administrative offices from the rest of the buildings…it was imperative that the entire camp be ready for inspection at all times. This camp was the showplace for the Phoenix, District. All official guests who came to visit the Phoenix District headquarters were escorted to South Mountain and Camp SP-3-A.

For a C.C.C. company recently stationed in a remote camp near Grand Canyon, assignment to a camp so close to Phoenix was a welcome prospect, even if it meant the attention of visiting dignitaries, but high-ranking officials weren’t the only potential drop-in guests at the South Mountain camps. The 1936 Phoenix District Annual noted that Company 2860 and camp SP-4-A were “always on display and always ever ready for inspection by that most critical inspector, The Public…” South Mountain Park was already becoming a popular visitor attraction in part because of the work of the C.C.C. and the enrollees were expected to keep up appearances at all times.

The Tunnel That Almost Was

One project did not materialize, despite having the unqualified support of the landscape architect assigned to work on C.C.C. projects in the park. Department of the Interior plans called for a 500-foot long tunnel through the mountain near the summit of Telegraph Pass, linked to a southern approach road. In a 1936 letter to the Parks Department in Phoenix, William H. Douglass, the landscape architect who took credit for the tunnel idea, expressed satisfaction at hearing the tunnel was still being considered. Douglass explained that upon receiving word to halt construction of the tunnel road, he and the camp superintendent instead put the C.C.C. enrollees on overtime to excavate the site and, just before the camp was to close for the season, they set off charges, “so they [the next work crew] had to go ahead with the new location or leave a scar in the side of the mountain.” Despite Douglass’ best effort, the tunnel and its southern approach road were never completed, though the idea continues to crop up even today when residents living on the south side of the park demand better access to their jobs near downtown Phoenix.

A Fitting Legacy

By 1942 when the C.C.C. was disbanded South Mountain had 40 miles of trails, 18 buildings, 15 ramadas and 164 fire pits, water facets and other improvements largely due to the work of C.C.C. enrollees. Today, South Mountain Park no longer sits at the edge of the city, but is instead surrounded by homes and businesses, and little remains of the camps in which the Soil Soldiers lived and worked. However, the work of Roosevelt’s conservation army lives on in the ramadas and hiking shelters that continue to benefit visitors to South Mountain, and a careful hiker may even find a star-shaped stone and concrete structure that served as the base of the camp flagpole nearly 70 years ago. Copyright 2007. Michael Smith

(A modified version of this article previously appeared in the South Mountain Villager.)

3 comments:

Hi Mike - its Steve from the CCC symposium - I spoke with PJ about your looking for the tunnel and was out there myself assessing the approaches. If they actually left a scar there, it is (as you know) pretty elusive. I think that if 500 feet of tunnel was needed, the best route is not up along the current trails on each side of the pass, but straight through the ridge from the roadway, going directly under the lookout. An access road on the south looks feasible, but there are certainly no traces on the ground, or in Google Earth. Still, I sure hope the story is true! Maybe it is an obvious work site after all, but not in the logical place we have been looking....

Hi Steve. Thank you for dropping by. I've recently been fortunate to receive photocopies of pictures from the National Archives and whoever took them in the 1930s marked the proposed tunnel site with an "x" on the picture. Using these images may help us pin down the tunnel dig. No question that the tunnel was started - we've got a letter from the landscape architect bragging about putting a double crew on the job to push the project forward even after the decision came down to do away with the tunnel.

We should have a CCC conference at the Park later this year and maybe try to pin down the tunnel location as part of the presentations!

Keep in touch!

Great Site Mike! Thank you for finding and posting all this great history. I just wanted you to know I have a blog dedicated to South Mountain that will eventually have some more info on the CCC activities. It's on blogspot and it's called southmountainhistory. I wasn' sure if I could include an address or not.

Post a Comment