In 1933 a conservation army trooped into the forests, fields and parks of this country to begin what would ultimately amount to some nine years of continuous work. The conservation army that undertook this peaceful occupation was Franklin Roosevelt’s Civilian Conservation Corps- the CCC. Among the results: trail systems in Grand Canyon, visitor amenities in Yellowstone, Shenandoah, and Acadia, improvements at Mesa Verde, Colossal Cave, and Colorado National Monument and forestry improvements in all of our national forests. And this only scratches the surface.

Historians and economists are mixed in their appraisals of FDR’s Depression-era New Deal. Some argue the many alphabet agencies created under the New Deal were a lifesaver to millions of Americans, while others point to the creation of so many government agencies and mark it as the rise of bigger government and the demise of personal self-sufficiency in our culture. Some experts have even argued that Roosevelt’s policies actually prolonged the Great Depression. My point here is not to argue the merits of the New Deal at large. I’m not an economist. I will never attempt to defend so large and grandiose an endeavor as the New Deal, but I’ll defend the record of the CCC against all comers. And I believe I can say without fear of contradiction that the Civilian Conservation Corps was the most successful, most popular and most fondly remembered of all New Deal programs.

The Emergency Conservation Work program, as the CCC was originally called, was part of Roosevelt’s first 100 days in office. From the time that it was initially introduced, the act that created the CCC took just eighteen days to get through congress and on March 31, 1933 President Roosevelt signed the bill into law. The measure under which the CCC was created was known simply as “an act for the relief of unemployment through the performance of useful public work.” There were no grandiose proclamations about saving the environment just the promise of gainful employment for single young men aged 17 to 28 years. Roosevelt hoped to avoid drawing workers out of the nation’s farms, fields and factories by focusing the effort on conservation. Roosevelt explained, “I propose to create a civilian conservation corps to be used in simple work, not interfering with the normal employment, and confining itself to forestry, the prevention of soil erosion, flood control, and similar projects…This enterprise will…conserve our precious natural resources. It will pay dividends to present and future generations. More important, however, than the material gains will be the moral and spiritual gains of such work.”[Emphasis added.] Roosevelt was referring to the “overwhelming majority of unemployed Americans…[who]…would infinitely prefer to work,” and perhaps more specifically to a vast army of unemployed youth who’d taken to the roads and rails in search of employment.

Roosevelt’s stated goal was to have 250,000 young men deployed to forestry camps across the nation by the spring of 1933. The goal seemed unattainable, but enthusiasm at the local level was immense. Within two weeks of the official creation of the CCC, Montana, Wyoming, Colorado and New Mexico informed the administration that 23,480 idle workers could be put to work in their states immediately. This figure applied to workers for national forest lands only; additional workers were needed for projects on state land and in National Parks as well.

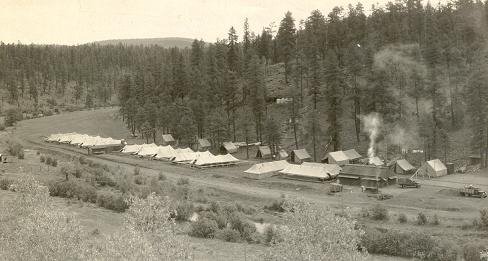

In a cooperative effort not seen before or since, the Departments of War, Labor, Agriculture, and the Interior, worked together to select suitable enrollees, provide the necessary medical checks and inoculations, issue supplies and work clothes and arrange transportation to the many camps scattered throughout the United States and its territories. Contrary to some notions, the CCC was not run by the military. The camps – usually home to about 200 enrollees – were placed under the command of a reserve military officer, but military discipline was prohibited and enrollees were only under general control of the commanding officer during their hours in camp. During the workday, enrollees labored and learned under the watchful eye of foremen and supervisors from the technical services such as the Forest Service, National Park Service, Bureau of Reclamation and the Soil Conservation Service.

Roosevelt’s initial enrollment goal was achieved and ultimately some 3 million young men passed through the ranks of the CCC between 1933 and 1942. For their six month enrollment, enrollees were housed, clothed, fed and paid $30 a month, of which as much as $25 was sent home to needy family members; after all, what good was $30 in the pocket of a lad living in a forest camp? What the economy needed was dollars to circulate and the CCC helped make that happen. The establishment of a CCC camp typically meant an additional $5,000 in monthly expenditures in the local marketplace. Some camp commanders, sensing that the presence of their camp was not fully appreciated by the local populace, used silver dollars to pay the enrollees their $5 monthly allowance, which was often quickly spent in the local town. Merchants, suddenly finding so many silver dollars in their cash registers, would quickly realize what a boon the nearby camp had become.

Nationwide, the work of the CCC is staggering even today. At civil war battlefields monuments were repaired and cleaned and the unheralded dead exhumed to be carefully placed in cemeteries. In our nation’s dust bowl region CCC enrollees worked on erosion control projects and shelterbelts. West of Denver, in a natural bowl of huge flanking red rock formations, CCC crews built Red Rocks Park and Amphitheater to take advantage of the natural acoustics in the magnificent geologic feature. The amphitheater continues to draw concertgoers today. In the Carolinas, young men worked with archaeologists researching prehistoric cultures. At the Mission La Purisima, a mission church originally constructed in the late 1700s in what is today Lompoc, California, enrollees were put to work rebuilding the ancient mission using largely the same tools and techniques used during the original construction. Young men worked redwood roof timbers with adze and axe. Other enrollees painstakingly recreated the proper texture on the exterior adobe. In a wood shop enrollees worked on reconstructing everything from the mission’s massive doors to handmade replicas of mission furniture. Indeed, the quest for authenticity was so strict that even ironwork like locks, keys, hinges, iron and brass lighting fixtures and iron nails were hand-forged.

Still other chores cropped up out of immediate necessity; for example, the use of CCC personnel to fight forest fires is a widely documented practice and several enrollees gave their lives in this effort. Search and rescue operations frequently took advantage of CCC manpower and enrollees gathered ticks for scientists studying Rocky Mountain spotted fever. All in a day’s work, an enrollee might learn how to sharpen tools, work in concrete and masonry, operate a jackhammer, set explosives or drive a caterpillar tractor.

In fiscal year 1937 alone the CCC built a total of 2,476 vehicle bridges, 11,559 miles of truck trails and they strung over 10,000 miles of telephone and power lines, largely to the benefit of our National Forests and National Parks. Multiplied over 9 years, these sorts of numbers become almost incomprehensible and the fact that we continue to derive benefit from this work almost three-quarters of a century later is unfathomable in our modern throwaway society.

In addition to gaining work skills training, many CCC enrollees were given an opportunity to continue their grade school and high school education, and some progressed to college level coursework by attending classes in the evenings. Additionally, a significant short-term benefit came out of the CCC program that has not been widely explored by historians. Experience in the CCC camps prepared many young men for their coming service in the military during World War II. Accustomed to some form of discipline and regimentation, knowledgeable in the rudiments of keeping their living quarters squared away, the former CCC enrollee-turned-GI Joe could get on with the more important tasks of training for combat. So, while many decried its quasi-military structure during the 1930s, many others would see the CCC as having been a valuable breaking-in period for the much rougher years from 1942 to 1945.

America’s entry into World War II following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 signaled the end of the CCC. Faced with a two-front war, and with America’s industrial complex gearing up for the war effort, congress failed to appropriate funds to keep the CCC working in the forests, fields and parks, and by the end of fiscal year 1943 the program was deemed fully liquidated. The “boys” of the CCC became the men of Corregidor, Midway, Anzio and Omaha Beach. Vocational skills gained in the CCC camps were put to use in our factories building tanks and airplanes. Nearly to a man, former CCC enrollees will tell you that the CCC was the best thing that ever happened to them, but as a nation we tend to remember more about the World War they fought between 1942 and 1945, than we do the quieter time from 1933 to 1942 when our nation was home to the Civilian Conservation Corps and its peaceful occupation. copyright 2007 Michael I. Smith

No comments:

Post a Comment