Aerial view of the Blackwater Fire, USFS Photo

Aerial view of the Blackwater Fire, USFS Photo(Note: There is no new scholarship here. This account of the Blackwater tragedy has been compiled from a number of sources, not the least of which are Timothy Cochran’s 1987 biography of Ranger Clayton and the detailed study of the fire done by Ranger Karl Brauneis, recently retired from the U.S. Forest Service. I’m especially indebted to Karl Brauneis who corresponded with me at length, providing background and his very useful professional insight into the event. A list of sources appears at the end of this post.)

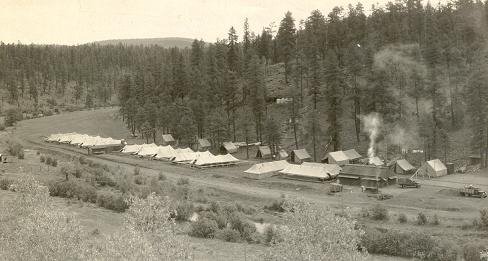

What came to be called the Blackwater fire started with a lighting strike in the Shoshone National Forest some time on Wednesday, August 18, 1937. The resulting fire smoldered and crept through the ground fuels for two days before it was reported by the owners of a local hunting camp. At nearly the same time, a spotter plane, observing another fire in a nearby basin, detected the smoke in the Blackwater Creek drainage and, upon landing, reported the approximately two acre fire to the Wapiti Ranger Station.

Fittingly, the first group of seven CCC enrollees arrived at the fire on their own initiative. Returning from a work detail, the men spotted the fire as it began to crown into the treetops. Unable to make contact with the local district ranger, Charles Fifield who was already working the fire, the CCC foreman set his men working to scrape a fire line at the base of the fire. Typically, local residents could be counted on to respond to a fire hazard, but with July and August the busy tourist months in the region, few felt inclined to leave their paying work at the hunting and tourist camps to fight a fire for meager wages. Additionally, the local cooperators may very well have felt, with some justification, that the local CCC camps could be counted on to adequately handle what otherwise would have been a community responsibility.

Shortly after 3:30 P.M. on August 20th, the Wapiti CCC camp was alerted and, according to one account, men from this camp were moving toward the fire within twenty minutes of receiving the alarm. Initially, the smoke was rising vertically from the area of Blackwater Creek, however as the rangers and CCC enrollees neared the fire the smoke and flame grew in intensity. Nightfall found Ranger Fifield, along with some seventy firefighters working to construct fire line around the blaze that had grown to 200 acres by 8:00 P.M. that night. Though winds were light, the canyons served to pump air to the blaze in a familiar scenario, and the forest crowned out in several places, pushing spot fires ahead of the main fire.

After meeting with rangers on the fire line at around 8:00 P.M., Shoshone Forest Supervisor John Sieker left to obtain additional men with the hope of having 150 men on the fire line by daylight. Among those requested were fifty men from the Tensleep CCC camp in the Big Horn National Forest. During the night two crews of roughly thirty men each were detailed to construct fire line around the flank of the fire in two directions extending out from Blackwater Creek. Daylight found 120 men working the fire, which had blown in a northeasterly direction, overtopping Trail Ridge to burn in green timber on the other side. The prevailing winds made this the area of concern, the “hot spot” as one ranger recalled.

The first fifty reinforcements, CCC enrollees from camp BR-7-W at Deaver, arrived at approximately 1:30 P.M. and, because they were relatively inexperienced, they were detailed to the quieter west sector to continue line construction and to offer partial relief for a crew that included CCC personnel from Yellowstone National Park. At approximately the same time, fifty-one CCC enrollees and Forest Service personnel from the CCC camp at Tensleep arrived and headed to a new sector to extend fire line northeasterly from Trail Ridge.

The Tensleep crew was comprised of CCC enrollees from Company 1811, which had been reassigned to Wyoming from Texas just three short months earlier. In Texas, the men of Company 1811 worked to create Bastrop State Park, establishing bridle paths, guest cottages and lakes for fishing. As was the case with many CCC companies, once the work in Bastrop State Park was finished, Company 1811 pulled up stakes and transferred to another camp for new work assignments. Usually reassignment involved moving to another camp in the same state, but entire companies were occasionally moved en masse from state to state. Consequently, in the summer of 1937 the men of Company 1811 found themselves far from their homes in Texas, living and working in a camp at 8,600 feet above sea level, in the shadow of snow capped Cloud Peak. Most would travel the same route back home when their time with the CCC was finished, but some would depart earlier, their bodies shipped home to grieving families.

The men from the Tensleep camp should have arrived at the Blackwater fire much earlier than the Deaver crew, however Supervisor Sieker’s request to have them on the fire by 8 A.M. did not pan out. First, there was an inexplicable three-hour phone delay in relaying the message to the Tensleep camp. To make matters worse, Sieker’s estimated travel time proved to be optimistic. The Tensleep crew, led by Junior Forester Paul Tyrrell and Foreman James Saban, left the Tensleep CCC camp early on the morning of August 21, 1937, and, after traveling more than 180 miles over rough roads in the dark, arrived at the Blackwater Creek supply camp around 11:30 that same morning. The crew was given a quick meal, outfitted with tools and lunches and marched toward the fire line with the foremen taking up positions at the front and rear of the column. A project superintendent from the Wapiti camp reported the men “were in good spirits and many joking remarks were passed back and forth” as the crew passed through the upper fire camp. At the upper fire camp the Tensleep crew was met by Forest Rangers Al Clayton and Urban Post. Clayton had been called up by Supervisor Sieker to take charge of the troublesome east fire line. Knowing the rough climb ahead, Ranger Post ordered the foremen to make certain the men only filled their backpack pumps half full before proceeding to the fire line with Ranger Post and Junior Forester Tyrrell leading and Ranger Clayton and foreman James Saban taking up the rear.

Post recalled that he and the crew passed through a group of Park Service and Bureau of Public Roads (BPR) workers before arriving at their place along the fire line. As the crew began to string out along the edge of the fire, they crossed a draw with a small trickle of water and Post detailed one man to remain and build a dam to impound water for the backpack pumps. Having been placed in charge of safety for the eastern fire sector, Clayton remained in the area of the stream, all the while monitoring the overall situation. With Clayton near the draw was Foreman Saban, Forest Technician Rex Hale from the Wapiti CCC camp and CCC enrollees David Thompson, John Gerdes, Will Griffith, Mack Mayabb, George Rodgers and Roy Bevins from the Tensleep camp. “Everyone was in good spirits,” Post reported afterward. “The day clear and quiet, the fire barely smoking – it appeared to be an easy task to get a line through the basin to timberline before sundown.” Post’s optimism was misplaced.

By about 3:15 P.M. Post, with the balance of the Tensleep crew had reached the end of the Bureau of Public Roads fire line and were strung out to continue the fire line. Post recalled afterward that the work ahead of them appeared to be quite simple: Extend the fire line to connect with a natural firebreak created by a rocky ridge to the northeast. As Post’s men set to work, the BPR crew was below their own fire line working to put out two small spot fires that had jumped the line.

At about the time Post’s men were setting about the task of fire line construction, Ranger Clayton, still near the spot where the Tensleep crew had begun its fire line under the supervision of Foreman Saban and Technician Hale, spotted the telltale sign of new smoke below the fire line. Recognizing the potential hazard of fire below the fire line crew, Clayton wrote a quick note and gave it to enrollee Thompson for delivery to Post:

Post, We are on the ridge in back of you and I am going down to the spot in the hole. It looks like it can carry on over the ridge east and north of you. If you can send any men, please do so, since there are only eight of us. Clayton.

Other crews and technical service personnel saw the same spot fire as well and preparations were being made to attack it from a number of directions when events spiraled out of control. At approximately 3:30 P.M. erratic winds blew the fire into the forest crown both above and below the fire line. What had been the simple task of establishing a fire line now became a hurried search for an escape route and a matter of life and death. Post quickly ran to the northwest, climbing a rocky outcropping to scout the fire’s progress. From his vantage, Post saw a spot fire growing to the north and northeast of his crew. Post decided to put some or all of his men on the new spot fire. Then, a sudden wind shift pushed the blaze back to the southwest and Post’s proactive response became a reactive response, and he ordered his crew to abandon the fire line and proceed in a northeasterly direction to the ridgeline.

In the midst of this confusion Thompson arrived with Clayton’s note. With 40 men in tow, including elements from the BPR crew, Post deemed it foolhardy to go back down into the fire. With shifting winds peaking at 45 miles per hour, and crown fires erupting overhead, Post made the only reasonable choice: take his men and run. Post would later write:

Tops of the trees swung in the strong wind which was coming up through the basin, spot fires developed between the large spot fire and the main fire, and the wind had reached our line almost at once, and the large fire was a furnace immediately….Some of us wait for Tyrrell and the last ones out. The smoke is thick, the air is hot; we hurry up the ridge. Heavy tools are left behind. We take lady shovels, Pulaski’s and canteens – we may need them for our own protection.

The fleeing crews reached an opening, or what Post referred to as a “small park” but the escape route was blocked by fire, which was also burning around to the south of the open refuge. As the men considered their few remaining options, the wind shifted again, causing the forest crown to ignite lower down the ridge and perilously close to the men and their open refuge.

All down on the ground! (Post recalled.) But some do not have time to respond. Red spots appear on faces, and skin is stripped from all exposed surfaces. The heat is terrific, and it seems unbearable, but we have no safer place. If this is the end, we must take it here.

In the heat, smoke, ash and panic, some of the men became unmanageable. Some refused to lay on the ground, preferring to take their chances with a dash through the blaze, while others sat up to say prayers. Junior Forester Tyrrell pinned three men to the ground, holding them still and shielding them from the heat.

As the smoke cleared, Post began to shift the men around the open park, avoiding each successive wave of heat and fire. The worst of the fire was over by 5:00 P.M. but the smoke remained so thick that Post and his men stayed in place for nearly three more hours before rising from their refuge to begin the painful walk out of the burn. Of the forty or so men trapped with Ranger Post, seven would die either on the spot or later from the burns they suffered. Among the dead, five CCC enrollees (4 of whom had attempted to run through the flames), one Bureau of Public Roads crewman and Junior Forester Paul Tyrrell who had struggled so valiantly with the panic-stricken men to shield and restrain them.

Precisely what happened to Ranger Al Clayton and the seven men left behind near the stream crossing is unclear because, of this group, there were no survivors. No doubt Clayton would have been mustering the men for an attack on the spot fire he detected below the fire line. A theory advanced by one of the fire investigators speculated that Clayton may have scouted ahead to check the spot fire, possibly taking some of the men with him, leaving the rest to wait for reinforcements from Post’s crew. In traveling down the gulch toward the spot fire, Clayton would not have had the unobstructed vantage enjoyed by Post and his crew and thus, would not have seen the blow up developing. Once the danger became apparent, Clayton and possibly his crew would have hurriedly turned back up gulch toward the streambed to seek refuge in its potentially cooler, wetter surroundings. Reportedly, the condition and location of Clayton’s body indicates he may have been late in getting back to the stream crossing, having returned from scouting the fire. If Clayton wasn’t leading his men back toward the stream bed, with its promise of cooler fresh air, he was in the act of collecting the men when the blow up overtook the entire group.

The bodies of Clayton and six of the men in his detachment were found lying within 30 feet of each other. Another enrollee, Roy Bevens was found badly burned within 60 feet of the others. As he was being evacuated, Bevens exclaimed, “God, how lucky I am to be alive.” He would later die of his injuries in a hospital in Cody, Wyoming.

In the immediate aftermath of the blow up and its tragic consequences, fire suppression work all but ceased as crews fanned out into the burn to search for victims. Ranger Clayton and the men in the gulch were discovered in the process of extricating Post’s group from the burn. With help from rescue parties, the scarred and fatigued survivors carried the dead and dying of Post’s group down to the lower fire camps where they were tended to before being transported to hospitals in Cody.

As fire fighting work resumed, the body of Ranger Al Clayton and the six men who died with him were removed in the late morning and early afternoon of August 22, 1937. A local newspaper reporter wrote of the scene:

Seven pack-horses, each with angular forms wrapped in canvas and lashed to the saddles, filed slowly out of the wooded ravine and stopped at the cars. Over a hundred wide-eyed, ashen-gray youngsters, just ready to go to the fire line, pushed forward, drawn by a chilling magnetism to see what their former comrades looked like.

New CCC crews continued to arrive until at one point more than 500 men were fighting the blaze. By noon on Tuesday, August 24th the fire was listed as officially under control and on the following day the Forest Service supervisors began to release CCC crews to return to their camps and their regular duties. Finally, on August 31st, ten days after the fatal blow up and almost two weeks after lightening started a seemingly inconsequential blaze, the last of the fire fighting crews were disbanded, having constructed more than eleven miles of fire line in the process of extinguishing the Blackwater Fire.

In the immediate aftermath of the Blackwater Fire, David P. Godwin of the Forest Service Division of Fire Control based in Washington, DC conducted the government investigation of the event. In his report, Godwin found little fault with the foremen and supervisor’s handling of the fire. Godwin’s attention focused on the travel times of the units reacting to the fire and specifically on the critical delay experienced by the crew from the Tensleep camp. Godwin speculated that, had they arrived as scheduled, the Tensleep crew would not have been deployed where they were when the fire blew up and thus may very well have survived unharmed.

In the immediate aftermath of the Blackwater Fire, David P. Godwin of the Forest Service Division of Fire Control based in Washington, DC conducted the government investigation of the event. In his report, Godwin found little fault with the foremen and supervisor’s handling of the fire. Godwin’s attention focused on the travel times of the units reacting to the fire and specifically on the critical delay experienced by the crew from the Tensleep camp. Godwin speculated that, had they arrived as scheduled, the Tensleep crew would not have been deployed where they were when the fire blew up and thus may very well have survived unharmed.Today, Godwin is remembered as the man who, just two years after the Blackwater fire, authorized the expenditure of funds to carry out parachute jumping experiments linked to fire suppression. To say that Godwin, the man who investigated the Blackwater fire, had a hand in the creation of what came to be known as the smokejumper program is not an overstatement. One has to wonder what role the Blackwater tragedy had in sharpening Godwin’s resolve to put crews on the fire line in rapid fashion, thus leading to his support for airborne suppression tactics.

*** *** ***

On August 21, 1939, beneath a cloudless Wyoming sky, more than 500 local residents and dignitaries gathered for the dedication of three monuments to the men who died fighting the Blackwater fire two years earlier. The first ceremony took place near the junction of Blackwater Creek and the Shoshone River, where a stone monument some 71 feet long bears the names of those killed in the nearby forest. During the dedication ceremony Burt Sullivan of the Bureau of Public roads was awarded the American Forestry Association fire medal for heroic service during the fire. Five months earlier, Ranger Urban Post received a similar medal for his actions in leading his men to safety. Prior to the Blackwater Fire, no medal for forest firefighting heroism existed.

Following the dedication ceremony at the large monument, a group of officials traveled on horseback to dedicate a smaller monument in the newly renamed Clayton Gulch. The smaller monument, like it’s larger companion some nine miles away, was constructed by CCC enrollees. A third monument at “Post Point” marks the spot where Ranger Post and his men sought refuge.

The role of fighting forest fires would remain the purview of the CCC until the U.S. entry into World War II spelled the end of the conservation work program. One chronicler of the CCC reported that forty-seven CCC enrollees lost their lives fighting forest fires between 1933 and 1942. In that period, the CCC devoted nearly 6.5 million days to fire suppression, or the equivalent of 16,000 men laboring for an entire year on an eight-hour day. The soldiers of Roosevelt’s Forest Army were quickly absorbed into the very real branches of the military, but in the final days, as congress debated whether or not to keep the program, one of the principal arguments for keeping the CCC in place was its use as a fire suppression force that would be especially useful during wartime.

The Blackwater fire was by no means the first or the last mass tragedy in the annals of forest fire history; indeed other fire events have taken a greater toll in lives lost. What sets the Blackwater fire apart is the fact that, for 70 years, the tragedy has remained in the shadows of history, overpowered by more recent events like Mann Gulch and Storm King. Of the dead of Mann Gulch, the elder MacLean wrote, “They were young and did not leave much behind them and need someone to remember them.” MacLean might just as well have been writing about the dead of Blackwater Creek, who, save for their foreman and leaders, have been largely lost to history.

Killed in the Blackwater Fire:

Alfred G. Clayton, Ranger

James T. Saban, Technical Foreman

Rex A. Hale, Jr. Assistant to the Technician

Paul E. Tyrrell, Jr. Forester

Billy Lea, Bureau of Public Roads Crewman

Enrollees:

Clyde Allen

Roy Bevins

Ambrogio Garcia

John B Gerdes

Will C. Griffith

Mack T. Mayabb

George Rodgers

Ernest Seelke

Rubin Sherry William Whitlock

“12 Die, 48 Injured As Forest Burns.” New York Times 23 August 1937: 8.

1937 Annual. Civilian Conservation Corps, Company 1811. No pub. No date.

Brian Ballou. “Blackwater Fire.” Wildland Firefighter February 2000.

Karl Brauneis. “1937 Blackwater Fire Investigation.” Static Line. Vol. 3 – Edition 4, July 1997.

Timothy S. Cochrane. “A Folk Biography of an United States Forest Service Ranger, Westerner, and Artist: A.G. Clayton.” PhD Dissertation Indiana University, 1987.

David P. Godwin. “The Handling of the Blackwater Fire.” Fire Control Notes. U.S. Department of Agriculture, U.S. Forest Service. December 6, 1937.

John MacLean. Fire on the Mountain. New York: William Morrow and Company, 1999.

Norman MacLean. Young Men and Fire. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992.

Stephen J. Pyne. “Flame and Fortune.” The New Republic 8 August 1994: 19-20.

Jack Richard. “Fire Line Hell.” Sports ‘Afield August 1941: 29+.

John A. Salmond. The Civilian Conservation Corps, 1933-1942: A New Deal Case Study (Durham: Duke University Press, 1967).

United States. Department of Agriculture, U.S. Forest Service. Rocky Mountain Bulletin Memorial Number Blackwater Fire. Vol. 20, No. 10: October 1937.

The barracks is Spartan – the CCC was not a summer pleasure camp. Noteworthy in this picture are the raincoats and laundry bags hung neatly by each bunk. Also of note is the nametag affixed to each bunk and the three heating stoves. Often the stoves were barely sufficient to keep the barracks warm and usually an enrollee was assigned the job of making sure the stoves kept burning all night.

The barracks is Spartan – the CCC was not a summer pleasure camp. Noteworthy in this picture are the raincoats and laundry bags hung neatly by each bunk. Also of note is the nametag affixed to each bunk and the three heating stoves. Often the stoves were barely sufficient to keep the barracks warm and usually an enrollee was assigned the job of making sure the stoves kept burning all night. In most camps, the reading room was usually a place for quiet study, letter writing and occasionally evening classes in forestry, leather crafts, mathematics or reading. The camp F-3-W library appears to have a good selection of magazines and you’ll note a sign that reads “Do It Now,” hanging from the ceiling.

In most camps, the reading room was usually a place for quiet study, letter writing and occasionally evening classes in forestry, leather crafts, mathematics or reading. The camp F-3-W library appears to have a good selection of magazines and you’ll note a sign that reads “Do It Now,” hanging from the ceiling.  Thus ends our virtual tour of Camp Riley Creek F-3-W in Fifield, Wisconsin. In pondering these young men as they looked in October 1940, it’s important to consider that many of them probably went into the military not too very long after these photos were taken. It’s sad to think that some of these bright, eager faces may not have returned from the World War they went off to fight. Likely, they would prefer that we remember them for their service in helping stamp out totalitarianism and we certainly do remember and honor their service, but we’d do well to also remember a more peaceful time that no doubt shaped their perceptions of democracy and fairness, ultimately leading to that most significant of sacrifices. We should also remember those who survived and went on to have useful, vital, productive lives. Certainly our thanks go out to all of them, the residents of this tidy little town near Fifield, Wisconsin.

Thus ends our virtual tour of Camp Riley Creek F-3-W in Fifield, Wisconsin. In pondering these young men as they looked in October 1940, it’s important to consider that many of them probably went into the military not too very long after these photos were taken. It’s sad to think that some of these bright, eager faces may not have returned from the World War they went off to fight. Likely, they would prefer that we remember them for their service in helping stamp out totalitarianism and we certainly do remember and honor their service, but we’d do well to also remember a more peaceful time that no doubt shaped their perceptions of democracy and fairness, ultimately leading to that most significant of sacrifices. We should also remember those who survived and went on to have useful, vital, productive lives. Certainly our thanks go out to all of them, the residents of this tidy little town near Fifield, Wisconsin.