Note: A longer version

of this article appeared in the May/June 2013 issue of Army Engineer magazine. I

have retained the original references list but retitled it “For Further

Reading” since some of the sources listed were not used for the portions of the

article that appears here. Also,

throughout this piece I refer to the “army” as the driving force behind the

mobilization and deployment of the CCC.

In fact the War Department was the military agency tasked with the job

of in-processing and caring for enrollees and the bulk of that task fell to the

Army, however you will find instances of CCC camps being run by Marine Corps

and Navy officers as well.

|

| Civilian Conservation Corps enrollees, Fort Knox conditioning camp, 1934. |

On March 24, 1933 the commanders of

all nine Army Corps areas received a secret radio communique, warning of a potential

task of national importance about to be delegated to them. No doubt the message was received with some

trepidation, angst and frustration, for the upshot of the broadcast was that

the United States Army should prepare for a mass mobilization of men that would

ultimately exceed that which was undertaken in connection with America’s

involvement in World War I. And yet,

while many in the military may have cursed their luck in early 1933, by years’

end many would agree with the sentiments of Colonel Duncan K. Major who,

writing in the July-August 1933 issue of Army

Ordnance, noted that “Few military campaigns have equaled such a

performance. To the Army it offered a

real opportunity.”

What sort of message

would cause the Corps area commanders to sit up and take notice? Anticipating passage of the bill to create

the Civilian Conservation Corps, the War Department sent word to all nine Corps

commanders, putting them on notice that the initial tasks of in-processing,

conditioning, organizing, equipping and transporting the new enrollees to their

respective railheads would fall to the Army.

From the outset, and even as the first enrollees began to roll in

following the passage of the legislation that created the CCC on March 31,

1933, the role of the Army was to have been limited, with control of the new

enrollees reverting to various technical services such as the Forest Service

and National Park Service at the earliest opportunity. Given the world situation and the state of

military preparedness in the United States in 1933, it is little wonder that

even this supposedly limited military role met with concern both within the

military and in civilian circles.

Many Americans,

wary of burgeoning militarism overseas and with memories of World War I still

fresh in their minds, opposed anything that smacked of increased militarism or

rearmament at home and the status of the United States military, ranked 17th in

the world, was a reflection of this broad sentiment. In 1933 most Army units were far from fully

staffed; George C. Marshall commanded a battalion that should have counted

upwards of 1,000 men on its roster but which in fact could muster barely 200

men. Not surprising then that within the

military ranks the postwar officer corps questioned, justifiably, the

military’s ability to undertake even a limited role in the mobilization of the

CCC while still maintaining any sort of national defense posture in the

process.

|

Letter to Cpt. James N. Luton, 323rd Infantry

informing him that his application for active

duty service with the CCC has been received. 1936. |

And yet, that is

exactly what happened, and more. When it

became clear that the agencies involved (Department of War, Department of

Labor, Department of Interior and Department of Agriculture) would be unable to

meet President Roosevelt’s goal of placing 250,000 young men in forestry camps

by July 1, 1933, under the original organizational matrix, the Army assumed

control of all matters except supervision of the work being done. With its expanded role, the Army reluctantly

found itself in charge of CCC enrollees all hours of the day except the time

they were away from the camp working for the technical service – approximately

eight hours a day, five days a week.

The increased Army

role cleared some of the logjams, but mobilizing and deploying enrollees

continued to lag behind and it remained clear that the President’s goal would still

not be met. Again the Army was called in

to formulate a plan. Given less than 40

hours, Colonel Duncan K. Major, the Army’s representative on the President’s

Advisory Council assembled sections from the General Staff and worked through

the day and night of May 11th and into the early hours of the 12th

to assemble the relevant facts, draw appropriate conclusions and propose a

suitable recommendation that concluded with the following blunt proposal:

It is therefore recommended that if

the decision is to place 274,375 men in work camps by July 1, 1933, the

Director give the War Department its full mission at once, provide the means

for its accomplishment and then protect it from all interference. The means to be provided are: 1. $46,000,000

to be transferred at once; 2. An Executive Order waiving restriction on

purchases; 3. The necessary instructions to the Department of Labor covering

selection.

The updated plan

was immediately approved by President Roosevelt and the impact of the Army’s

further expanded role and greater discretionary power was almost immediate. Whereas just 52,000 young men had been

enrolled in the CCC by May 10th, national enrollment jumped to over

62,000 by May 16th, increased by another 8,100 men on the 17th

and further increased by 10,500 men on the 18th of May. Ultimately, the President’s goal to have a

quarter million enrollees working in more than 1,000 camps by July 1, 1933 was

met because the Army was given greater flexibility and the massive effort

decentralized down to the level of the nine Corps areas. In an article in the January-February 1934

issue of The Military Engineer Major

John Guthrie, Corps of Engineers, reported the results of that effort with

pride:

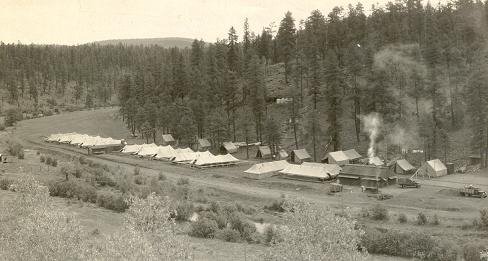

This whole movement was an

unprecedented mobilization. An average

of 8,450 men per day was enrolled. To

accomplish the movements from conditioning camps (Army posts) to work camps,

211 special trains were used, carrying 64,196 men in 1,605 sleepers and

coaches; of these, 55,130 men went from Corps Areas I, II, and III to the far

west. To equip and supply this tree Army

of 314,000 men has been a tremendous job in itself.

The effort truly

was unprecedented, but it was a drain on the Army’s resources. All but two Army schools were closed, their

faculty and students mobilized for duty with the Civilian Conservation Corps. Of the 9,936 regular Army officers available

when the CCC was established, 5,239 were called up for full time service

related to the CCC, but there was satisfaction in a job well done and by

mid-1933, even Colonel Major, initially a skeptic, was moved to write glowingly

of the CCC mobilization for Army Ordnance.

|

Regular Army officers and an NCO at Camp Roosevelt,

the first CCC camp, 1933.

|

History records

the War Department’s nearly decade long association with the CCC as an

unparalleled success and despite rough patches, especially in the early months,

and despite the public’s initial fear that the CCC would somehow become

“militarized” by its connection to the Army, media accounts of the CCC

eventually became heavy with military metaphors (“tree Army,” “soil soldiers,”

“forests protected by ‘shock troops’ of the CCC”) and by the early 1940s the

CCC’s effort was refocused on national defense work as the economy improved and

enrollment declined, but always with an eye toward improving the enrollee, too.

Eventually,

active duty officers were rotated out of CCC service, replaced by reserve

officers from all branches of the military, many of them eager for an

opportunity to hone their leadership skills and often out of work in their

civilian professions, much like the enrollees in the camps they came to

lead. Despite the odd difficulty or

adversity in the local camps all the way up to the Corps level, the record of

the Army and the War Department in connection with the CCC is unmatched in our

history. The largest peacetime

mobilization, the sustained deployment and provisioning of a peacetime

conservation Army over nearly a decade and tangible improvements in military

readiness are the legacy of the Army’s association with the Civilian

Conservation Corps. Military officers,

active duty and reservists, gained valuable experience leading company-sized

units, learned to manage and account for equipment, experienced the sad duty of

dealing with sick, injured and dead enrollees and perhaps just as importantly,

served as positive models for millions of men who became veterans in their own

right because of the U.S. entry into World War II. While there are no hard and fast figures to

show how many CCC enrollees went on to serve in the military, one recent

history claims the number may be as high as 90 percent. Even if one estimates the number of enrollees

who entered the military at a more conservative 50 percent, it still must be

acknowledged that the other 50 percent likely entered the home front workforce

where they put their newly learned job skills to very good use in support of

the war effort. In any event, the

significance of the CCC is unquestionable and the role of the U.S. Army in the

success of the CCC is equally undeniable.

Little wonder then that no less a figure than General George C.

Marshall, himself a CCC district commander, a World War II leader, Secretary of

State and Nobel Prize recipient said of the Civilian Conservation Corps: “I found the CCC the most instructive service

I have ever had and the most interesting.”

|

| Military staff at a CCC camp in Wisconsin. |

|

| Phoenix CCC District staff, 1936. |

For Further Reading

Captain “X”, “A

Civilian Army in the Woods,” Harper’s

Monthly Magazine, March 1934, 487-497.

Coffman, Edward M.,

The Regulars: The American Army 1898-1941 (Cambridge,

MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard

University Press).

Guthrie, John D.,

“The Civilian Conservation Corps,” The

Military Engineer, Jan-Feb, 1934, Vol. XXVI No. 145, 15-19.

Johnson, Charles

W., “The Army and the Civilian Conservation Corps, 1933-42,” Prologue: The Journal of the National

Archives, Fall 1972, 138-156.

Maher, Neil M., Nature’s New Deal (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008).

Major, Duncan K.,

“Mobilizing the Conservation Corps: The Army

Does a Gigantic Job in Record Time,” Army

Ordnance, July-Aug, 1933, Vol. XIV No.79, 33-38.

Mays-Smith, Kathy, Gold Medal CCC Company 1538 (Paducah,

KY, Turner Publishing Company, 2001).

McKoy, Kathleen L.,

Cultures at a Crossroads: An Administrative History of Pipe Springs

National Monument (Denver, CO: U.S.

Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 2000).

Pasquill, Robert, The Civilian Conservation Corps in Alabama, 1933-1942: A Great and Lasting Good (Tuscaloosa,

AL: University of Alabama Press, 2008).

Salmond, John A., The Civilian Conservation Corps,

1933-1942: A New Deal Case Study

(Durham, NC: Duke University Press,

1967).

Whittlesey, Lee H.,

Death in Yellowstone: Accidents and Foolhardiness in the First

National Park (Lanham, MD: Roberts

Rinehart Publishers, 1995).

Images from the

author’s collection.

© Michael I.

Smith, 2013