CCC Fire Fighting Crew Photo Courtesy of NACCCA

CCC Fire Fighting Crew Photo Courtesy of NACCCAThey were young and did not leave much behind them and need someone to remember them.

---- Norman McLean, Young Men and Fire

---- Norman McLean, Young Men and Fire

(Note: August 2007 marks the 70th anniversary of the single deadliest day for Civilian Conservation Corps enrollees on the fire lines during the Great Depression: the Blackwater Fire in Wyoming's Shoshone National Forest. This editorial explores the possible reasons why the event has not received the popular and scholarly attention that other similar events have received. A detailed account of the Blackwater Fire will be posted in the near future.)

In the somewhat limited canon of forest fire history, two seminal events are taken out and dusted off every summer when the western United States is under threat of a major forest fire blowup: the Mann Gulch Fire of 1949 and the Storm King Mountain Fire of 1994. To the unenlightened, Mann Gulch and Storm King roll off the tongue like the names of long-dead jazz musicians but to historians and students of fire science they are written and spoken of with reverence. As fire history, Mann Gulch and Storm King have held their own not simply because each fire event claimed the lives of men and women who were sent to fight them. Mann Gulch and Storm King offered valuable lessons for any fire professionals willing to pay attention. Add the fact that each fire has been the subject of a book length treatment, and the rest is history as they say.

Mann Gulch and Storm King have arisen from their own smoke and ash into bright sunlight thanks to the masterful work of Norman and John MacLean, a father and son duo who transformed the events into battlefield engagements, fought by heroic professionals, and the battle’s aftermath into crackling good storytelling and a search for answers. In Young Men and Fire, the elder MacLean, in the roll of storyteller, led his readers up the steep slope of Mann Gulch with a group of fleeing smokejumpers, past their foreman’s improbable escape fire, to a gap in the rocks beyond which three would pass, but only two would survive. Their foreman lay down in the smoking remains of his escape fire and survived, as did two of the quickest smokejumpers. The rest burned where they fell, their wristwatches and personal effects blown upslope by the force of the fire’s hurricane winds.

In Fire on the Mountain, Norman MacLean’s journalist son John led us down a Colorado fire line in the midst of the 1994 Storm King fire, and then in a rush, back up the slope in the face of a torrential blow up, then ultimately, out into a different kind of blow up as one public agency pointed the finger at another. Again, professional firefighters, this time smokejumpers and hot shot crewmembers died in a losing uphill race against a blowup, but at Storm King there was a new, cruel twist: among the dead were women firefighters.

There has been no such redeeming reportage for the 1937 Blackwater fire, an equally costly and no less tragic event that killed 10 Civilian Conservation Corps enrollees and four of their technical service supervisors just eleven years before the Mann Gulch disaster. Why? Consider the overarching national emergency of the Great Depression and there is little wonder why the dead of Blackwater Creek do not seem to speak as loudly as their brothers and sisters in arms who have perished on the fire line since. Additionally, we might do well to remember that in 1937 Americans didn’t grieve so openly and, like it or not, men weren’t required to cry.

There may be one really good reason the dead of Blackwater Creek have not received the scholarly and popular acclaim accorded those who died at Mann Gulch and Storm King. Despite Norman MacLean’s argument to the contrary, historians really are little more than storytellers. Consequently, history favors the glamorous. History favors the swashbuckler who swings down from on high to fight dangerous foes using cunning and bravery. Storytellers prefer to recount tales of brave young men and women who enter a particular profession because they are brave and because they seek to be tested. The story of the Blackwater fire has no swashbucklers and no such tales of youngsters striving to stare down the ultimate test. With the exception of the forestry personnel, the dead of Blackwater were not professional firefighters. The boys who marched into Blackwater Creek on August 21, 1937 were enrollees in the Civilian Conservation Corps, a workfare relief program designed to keep young men off the streets and out of trouble, while teaching them a trade if possible. There is little glory in being out of work. History remembers the well trained and elite smokejumper, not the barely post-pubescent CCC enrollee who earned thirty bucks a month with orders to send twenty-five of it home to needy family members.

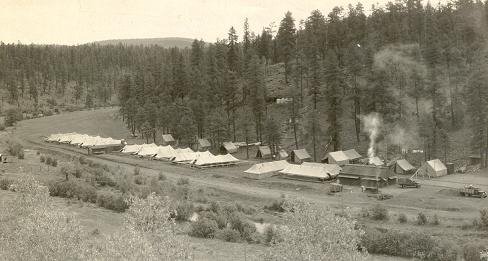

Nevertheless there was an air of esprit about the CCC boys who battled fire in a Wyoming forest so far from their homes in Texas. Mustered like soldiers, garrisoned like fighting troops, their personal time overseen by the watchful eye of army officers, they lacked only the mantle of elite professionalism carried by so many of their successors. Although their degree of training varied from camp to camp, CCC enrollees could be relied upon to be sober and hard working, especially when supervised by knowledgeable government personnel. For all their potential weaknesses, including the fact that many were barely out of their teens, the argument could still be made that not before, nor since the CCC, has the United States had a larger, more easily deployed fire suppression force on active standby. Further, one could argue that the fire suppression work of the CCC has existed in the shadow of the smokejumpers and hotshot crews who came after.

It is estimated that between 1933 and 1942, some 3 million young men passed through the ranks of the Civilian Conservation Corps, many on their way to a bigger, more deadly blowup in an overseas world war that would come to make their CCC service pale in comparison. No hard figures have been kept, but it is estimated that in 9 years some 57 CCC enrollees died fighting forest fires: ten at Blackwater in Wyoming, seven near Emporia, Pennsylvania, five near Orovada, Nevada and dozens of others anonymously, individually in forests across the nation, often far from their own homes and families. In his heart-wrenching book about the Mann Gulch fire, Norman McLean wrote that the dead smokejumpers of Mann Gulch were young and needed someone to remember them. We would do well to remember the equally young, if somewhat less glamorous enrollees of the Civilian Conservation Corps who fought fire and died in the forest in a time before anyone seemed to take notice of such things.

(© Michael I. Smith, 2007)

4 comments:

I know this post is old - but I just came across it while googling the Blackwater fire. I worked on the Shoshone for a couple seasons and lived not too far from the roadside memorial. We participated in a staff ride for the fire each year - if you ever get up that way and like to hike, it's worth it. I'm glad I found your blog as I've long admired the CCC efforts.

It's always bothered me that the Blackwater fire receives little attention and rarely do I meet a firefighter who is familiar with it. It is a fire that does have heroes - Karl Brauneis (retired) and Chris Schow did a tremendous job of bringing this fire to life for us the first time we explored it. The firefighters on the Shoshone will ALWAYS remember Blackwater....

I recently visited my Grandfather in a nursing home in California, and he told me about something that happened when he was in the CCC. I don't know what year or where, but he was part of a ground crew fighting a fire, when the fire jumped over a ridge unexpectedly and sent him and his crew into a creek, where they stayed for a full day. I wish I knew more details, and will try to get them.

I was surprised to find this blog so shortly after hearing the story.

Lesley Mays

Absolutely wonderful post, Micheal. I will be up there August 21, 2012 for the 75th and I know I won't be alone.

My Great Uncle is Paul Tyrrell who per Ranger Post's account of that day, pinned down three men shielding them...these three men all survived...my Great Uncle died 4 days later from his injuries sustained during the fire. He was the last of the 15 that died.

In an article I read, "During the dedication ceremony Burt Sullivan of the Bureau of Public roads was awarded the American Forestry Association fire medal for heroic service during the fire. Five months earlier, Ranger Urban Post received a similar medal for his actions in leading his men to safety. Prior to the Blackwater Fire, no medal for forest firefighting heroism existed." yet , no mention of my Uncle receiving anything posthumously for saving three lives that day...which would have been wonderful for his parents and brother to have.

Anyway, long time ago...and was nice to read the articles. I have never been to see the Monument didn't even know where it was until today. Typed in Fire monument near Cody Wyoming and all of this information came up. My grandfather told me this story about my Uncle saving lives when i was young, all my life I have remembered it, recounted it and now I have more information

Post a Comment