The recently released book The Forgotten Man by Amity Shlaes, is touted as an honest reappraisal of Roosevelt’s New Deal and, while I have not yet read it, I’ll go out on a limb here and state that if Ms. Shlaes attempts to use the Civilian Conservation Corps as an example of how the New Deal failed, she’d better not rely on the likes of other “historians” who’ve argued likewise. For example, she’d be smart avoid relying on Jim Powell for information on the CCC. (Shlaes website: http://www.amityshlaes.com/)

Jim Powell’s flaccid attempt to tar the CCC in his book FDR’s Folly is a good example of revisionist history run amok. As indicated in its subtitle, Powell’s book outlines, “How Roosevelt and his New Deal prolonged the Great Depression.” FDR’s Folly contains only 3 references to the CCC and for all that, Jim Powell would have been better off ignoring the CCC altogether.

Powell’s first reference to the CCC is a somewhat benign statement linking Roosevelt’s policies as governor of New York to his later creation of the CCC. Pretty simple. However, Powell’s other two references to the CCC step carefully across a line to imply something more. Powell notes that the CCC “was one of FDR’s first proposals for relief, offered March 9, 1933.” Then, as if casting about for something negative to say, Powell goes on to state that because labor organizations disliked the $1 a day wage being proposed, “the CCC wasn’t signed into law until March 31.” Okay, so it took 22 days to get the CCC proposal from vision to reality. By today’s standards, when new legislation passes through the House and the Senate at a glacial pace, the legislation creating the CCC was a model of speed and efficiency! Is Jim Powell aware that Roosevelt’s first 100 days are the standard by which all other administrations have been judged? Perhaps Mr. Powell thinks it should be the “First 50 Days.”

Mr. Powell then goes on to vaguely outline how the CCC was run, “very much like the army,” with enrollees reporting to “army training camps” before being assigned to companies under “…corresponding army commands.” “The men wore army uniforms, were driven around in army trucks, slept in military-style open barracks and were commanded by regular and reserve military officers as well as civilian CCC officers.”

Clearly Jim Powell is troubled by the military involvement in the CCC. Had he bothered to do some real research into the CCC, Mr. Powell would have learned that in 1933 the average American was easily as reticent about the military’s involvement in the CCC as he seems to be – if not more so. Had Mr. Powell bothered to check, he would have learned that CCC director Robert Fechner attempted to move forward with as little military involvement as possible in 1933, but when it became obvious that he couldn’t meet the enrollment goals set forth by the president, the War Department was called upon to ratchet up their participation to better speed the process of feeding, equipping and transporting the first 250,000 new enrollees. As it turned out, the military effort in connection with the mobilization of the CCC was excellent preparation for our later involvement in a world conflict.

As for army uniforms and army trucks, the uniforms were World War I surplus and in fairly short order the transportation was largely handled by the technical agencies like the U. S. Forest Service, National Park Service and the Soil Conservation Service, with CCC enrollees (not army personnel) doing the driving. And when it comes to active and reserve military commanders, Mr. Powell failed to point out that active duty commanders were replaced with reserve officers, many of whom had been put out of work themselves, so they had more in common with the enrollees than with their active military brethren.

Not content to put a stain on the CCC by implication, Mr. Powell then purports to outline some of the work done by the CCC and the statement is cynical enough to be worth quoting at length:

“The CCC men worked primarily in wilderness areas planting trees, trying to control tree diseases, and building fire towers and truck trails that might be used for fighting forest fires…CCC officials claimed they imparted useful skills like reading. The CCC was expensive, costing over $2 billion between 1933 and 1939, and a disproportionate amount of money went to western states.” (Emphasis added.)

So in Mr. Powell’s assessment the CCC tried to control tree diseases (where no meaningful effort had been made previously) and they constructed improvements that might be used for fighting forest fires. Furthermore, officials “claimed” that the program imparted useful skills, “like reading.” I’ll assume that Mr. Powell does in fact believe reading to be a useful skill. Again, had he bothered to look at some facts, Mr. Powell would have learned that in addition to reading, enrollees learned valuable work skills and discipline that they carried with them the rest of their lives. Many enrollees would go on to have life-long employment based upon skills they gained in the CCC. As for the question of whether or not the work of the CCC was useful in fighting forest fires, the statistics show a marked decline in the occurrence of forest fires during the years that the CCC was in operation and many of their forest roads are still in use today. Dozens of CCC enrollees died while fighting forest fires; a fact that Mr. Powell apparently failed to dig up in his very limited research.

Mr. Powell closes the statement by claiming a disproportionate distribution of CCC funds. The claim is vague enough that it will escape scrutiny by most readers. What does Mr. Powell mean when he refers to “money” that went disproportionately to western states. If a larger amount of funds for CCC work went to western states, it’s because a larger chunk of the public domain is in the west. If Mr. Powell takes enrollee allotments into consideration, then he’s way off the mark. While a majority of the physical and aesthetic improvements took place in western states, a good number of enrollees came from large eastern cities. These enrollees were required to send as much as $25 of their $30 monthly allotment home to their families back east. If we compare total enrollments by state for fiscal year 1937 for example, we see that 3,863 Coloradoans were enrolled, 1,468 Arizonans were enrolled, and 8,411 Californian were enrolled. By comparison, 16,697 New Yorkers were enrolled, 12,646 Pennsylvanians were enrolled, and 11,973 enrollees hailed from Massachusetts. So, if we talk simply in terms of work done and improvements made, it could be argued that the western United States benefited more from the work of the CCC than did the rest of the country. However, if we consider where the bulk of enrollment took place and thus where the enrollment benefits were going, we’ll see that the eastern states gained their share of benefit from the CCC as well.

Jim Powell’s final comment regarding the CCC involves an “embarrassing” episode involving Henry Ford, who was an ardent opponent of the National Recovery Administration. It seems Mr. Ford refused to sign on to the NRA’s automobile code. Nevertheless, when the CCC ordered 500 trucks, Ford’s bid was $169,000 less than the next lowest bid from Dodge. In the end, Mr. Powell reports, the CCC went with Ford’s lowest bid, and the reader is left to puzzle a bit over what the real scandal was exactly. Again, had Mr. Powell done any meaningful research in connection with the CCC, he would have leaned about the infamous 1933 “toilet kit scandal” and it’s implication of CCC bid-rigging. Furthermore, Mr. Powell doesn’t bother to explain why the CCC accepted bids for trucks if the army was doing all the driving, as he claims in an earlier section of the book.

Admittedly, Jim Powell’s book isn’t about the CCC exclusively, but given the paltry research done to back his claims, Jim Powell would have done well to leave the CCC out of his book. Furthermore, the flimsy arguments Mr. Powell uses to attack the credibility and usefulness of the CCC, call into question the arguments he uses to attack the rest of Roosevelt’s New Deal.

Amity Shlaes’ new book has come out to rave reviews. It will be interesting to see how she addresses the CCC in her appraisal of the New Deal. Frankly, without new, meaningful research to support it, no meaningful case can be made against the New Deal using the CCC as an example. In short: Criticize the New Deal to your heart’s content, but don’t hang your argument on the Civilian Conservation Corps.

(Copyright 2007, Michael Smith)

Monday, July 30, 2007

The Folly of Revisionist History

Posted by

Michael

at

7:58 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Amity Shlaes, Criticism, Editorial, Jim Powell, Revisionist

Thursday, July 26, 2007

"Hey, accidents happen!": Drunken Driving, Foul Balls and Mechanical Defects

Historians are really just storytellers. The best historians are those who can find the best stories, without having to resort to embellishment or revisionism after the fact. In the years and decades to come, historians, researchers, scholars and avid students of the Civilian Conservation Corps will eventually turn their attention to more obscure source material, in an effort to recount new and better stories about to the CCC. The realm of CCC history is a wide-open field for research and many are beginning to see that, especially as the 1941-1945 war years become evermore burnt over from a historical research standpoint. Future storytellers may be rewarded with some interesting insights into lesser-known aspects of the CCC and from time to time they may even get a chuckle out of what they find.

For example, in 1935, 1936 and 1937, there came up for discussion a number of Senate reports entitled “Settlement of Individual Claims for Personal Property Lost or Damaged From the Activities of the Civilian Conservation Corps.” These reports are basically a listing of claims made by regular citizens against the government, seeking reimbursement for damages received as the result of CCC activity. Understandably, nearly all of the claims in the 1935-37 period were the result of vehicular mishaps.

.JPG) Each of the incidents is noted to have been investigated by a board of officers who then made their recommendations regarding payment of claims and in some cases, fixing partial blame on the CCC enrollee. In only one case does it appear that full responsibility was placed on the head of the unfortunate CCC enrollee. On November 26, 1933 – perhaps in connection with Thanksgiving festivities that year – an intoxicated CCC enrollee, operating a CCC truck on the streets of Grand Junction, Colorado, “struck and damaged” a legally parked automobile belonging to one Andy McKelvey. “The operator of the truck,” the report states, “was apprehended, tried, found guilty, and confined as a result…” Mr. McKelvey received the princely sum of $65.35 “on account of damages sustained.”

Each of the incidents is noted to have been investigated by a board of officers who then made their recommendations regarding payment of claims and in some cases, fixing partial blame on the CCC enrollee. In only one case does it appear that full responsibility was placed on the head of the unfortunate CCC enrollee. On November 26, 1933 – perhaps in connection with Thanksgiving festivities that year – an intoxicated CCC enrollee, operating a CCC truck on the streets of Grand Junction, Colorado, “struck and damaged” a legally parked automobile belonging to one Andy McKelvey. “The operator of the truck,” the report states, “was apprehended, tried, found guilty, and confined as a result…” Mr. McKelvey received the princely sum of $65.35 “on account of damages sustained.”Bureaucratic red tape is nothing new and in the CCC there existed a strict set of guidelines and particular forms that had to be filled out in the event of an accident involving a CCC enrollee or vehicle. In the Manual of Administration for the Civilian Conservation Corps, written as a how-to guide by Army Lieutenant L.P.D. Warren in 1935, there is printed a sample copy of an investigation report. Lieutenant Warren points out in his text that if the owner of the private vehicle expresses their intention to file a claim against the government for damages, they were required to fill out Quartermaster Corps (QMC) Form #28, five copies of which would accompany the report of the investigating officer, but the Form #28 would not be listed as an attachment to the report. Other forms that were to be included and listed as attachments were the driver’s report of accident Form #26 and the investigating officer’s report Form #27.

Ironically, in Lt. Warren’s manual, there also appears a sample accident report for a mishap involving a CCC truck from a Soil Conservation Corps CCC camp at Athens, Georgia on May 4, 1935. It seems that on that day, government Dodge truck #32341, driven by Enrollee “X” (I’ll protect his name. He might be a member of a CCC veteran in your home town.) collided with a vehicle owned and driven by Mr. Ramey Epps of Athens, Georgia. Although the truck was listed as being on “official business” from Camp SCS-1, it was determined that Enrollee “X” was under the influence of intoxicants and he was found fully responsible for the accident. As a result, Enrollee “X” was required to pay $4.00 to cover the cost of repairing the government vehicle. The investigating officer’s recommendation that Enrollee “X” also pay $13. 35 to cover repairs to the privately owned vehicle was overturned by the District Headquarters.

Most of the incidents cited in the Senate reports don’t include things as salacious as drunken CCC enrollees cruising the streets of America’s cities looking for things to bang into, in fact most of the accidents are chalked up to bad road conditions and a condition generally referred to as a “mechanical defect.” For example a vehicle belonging to a Frank W. Brunner of Springfield, Illinois was damaged to the tune of $38.55, “when, due to a mechanical defect in the front wheels” the operator of a CCC truck struck and damaged Mr. Brunner’s car. In another incident involving a CCC truck outside Minersville, California, “the clevise (sic) pin sheared off,” leaving the CCC vehicle out of control, at which point it collided with a privately owned automobile causing $49.10 in damages. “Mechanical defect” was also along for the ride when Miss Lucy Ahrens’ vehicle was damaged due to a collision with a CCC vehicle in Tacoma, Washington on May 14, 1935.

Not all mishaps involving the CCC and damage to vehicles were the result of drunkenness, mechanical defect or treacherous road conditions. On April 14, 1935, Mrs. Clara B. Chapman was proceeding east on State Highway Number 103 in Van Buren, Missouri. Mrs. Chapman passed Big Spring Park as a group of CCC enrollees were engaged in baseball batting practice – as part of the authorized athletic program of Company 1740, the report is careful to point out. A foul ball struck Mrs. Chapman’s car “damaging it to the extent of $15.10.” One has to wonder how a foul ball can cause $15.10 worth of damage while other claims involving the collision of trucks with private vehicles occasionally resulted in claims as low as $7.90.

Finally, there is the Senate report involving a claim filed by H. C. Ledford of Randle, Washington. Here it seems fitting to quote the entry as it appears in the report:

“On May 4, 1935, the operator of a Civilian Conservation Corps truck, while proceeding in a westerly direction on Lower Cispus Road, near Randle, Wash., at approximately 25 miles an hour, attempted to stop after being hailed by boys who were driving a herd of cattle. Upon applying the brakes the pin sheared off, causing the operator to lose control of his vehicle, which collided with two cows, property of the claimant, damaging one of them to the extent of $20.”

How would one determine if a cow had been “damaged,” exactly? Furthermore, with the price of meat what it is today, I wonder if it’s still possible to only do $20 worth of “damage” to a cow.

So, what’s the lesson in all this? Storytellers – historians – aren’t always interested in portraying the entire story if one piece of it will suit their needs. For example, it’s become fashionable among scholars and academics to argue that Pearl Harbor was somehow the United States’ fault and that Hiroshima was simply an act of barbarism perpetrated on an already beaten Japanese nation. Do you think that our CCC history will be immune from such slanders in the years to come?

Taken as a whole, the Senate reports on payment of claims due to accidents involving the CCC are a useful insight into the workings of our government and they offer a glimpse of how things were handled in the camps. Picked apart and taken selectively, the reports might be construed to show that CCC enrollees were a bunch of boozing truckers, rumbling around the nation in vehicles rife with “mechanical defects” and thus not fit to drive.

The story of the CCC is your story but it will only serve for good if you tell the story. When grandchildren, nieces and nephews, sons and daughters ask you to tell of your time in the CCC, they’re asking because they want to know and that’s reason enough to tell the story. However there will be a bigger purpose to the telling in years to come when those memories take the form of oral histories and personal narratives that historians use to recount the story of Roosevelt’s Conservation Corps. Sure, tell the whole story, warts and all, and good historians - storytellers who are faithful to the trade - will accurately recount what you accomplished in a worldwide economic depression and a World War, while perhaps adding that no CCC enrollee was perfect.

Copyright 2007, Michael Smith (This article appeared in a slightly modified format in the NACCCA Journal.)

Posted by

Michael

at

7:54 PM

0

comments

![]()

Sunday, July 22, 2007

The Soil Army Invades Phoenix South Mountain Park

Given its quiet beauty today, it’s hard to believe that South Mountain Park played host to some 4,000 members of a peacetime conservation army between 1933 and 1940, but that is the fact of the matter. Indeed, without this peaceful occupation by self-proclaimed “Soil Soldiers,” Phoenix South Mountain Park would not exist as we know it today.

When Franklin Roosevelt assumed the office of president in 1933, America was in its fourth year of what has come to be called The Great Depression. Fully one-quarter of the population was without work and some 2 million young men and women are believed to have taken to the road in search of work and a meaningful future. Rightly or wrongly, many grew fearful that this wandering generation would fall into mischief or worse, under the spell of agitators. Action was needed and fast.

Among the many programs created in the first 100 days of Roosevelt’s fledgling New Deal was the Emergency Conservation Work program, which came to be known as the Civilian Conservation Corps – the C.C.C. Open to young, single men aged 17 to 28, the C.C.C. mobilized over 250,000 enrollees in the spring of 1933 and by the time the program was discontinued following the attack on Pearl Harbor, some 3 million young men served in the program, working in camps in every state and territory of the United States. Arizona saw its share of benefit from the labor of the C.C.C. On average 50 camps operated in the state and by 1942 some 41, 362 Arizona men received valuable employment and training in the C.C.C.

The Camp That Almost Wasn’t

South Mountain was a likely candidate for placement of a C.C.C. camp when the second phase of work began in the fall of 1933. Little had been done to improve what was then known as Phoenix Mountain Park following its creation in the 1920s so the area seemed a natural fit for the establishment of a C.C.C. camp to perform useful work and create valuable improvements. Nevertheless, there was a snag. The government mandated that C.C.C. camps must possess a source of potable water. In 1933, Phoenix Mountain Park lay some 8 miles outside the Phoenix city limits and possessed no viable source of water.

The city balked at the idea of providing a water supply for the then remote park site so Phoenix’s application for a C.C.C. camp was denied. There the matter might have rested if not for the intervention of Senator Carl Hayden who contacted the Office of National Parks, Buildings and Reservations to assure them that the $5,100 needed to provide a water supply would be taken care of. Senator Hayden was able to impress upon city officials the important potential benefits of having a C.C.C. camp at the park and on October 25, 1933, the Arizona Republic proclaimed “Opening of Mountain Park Well Assures Corps Camp.”

The Showplace Camps

Senator Hayden’s efforts paid out in spades because South Mountain was actually allotted two C.C.C. camps, designated SP-3-A and SP-4-A. The establishment of two camps so close to Phoenix can be traced to a request from the Secretary of the Interior to the director of the C.C.C. asking that some camps be established in areas adjacent to population centers. The proximity to a major city meant that the South Mountain Park C.C.C. camps became the showpiece camps of the Phoenix District, with civic leaders and dignitaries dropping by seemingly without notice.

Louis Purvis, an enrollee who transferred to South Mountain with the rest of his C.C.C company from a camp at Grand Canyon in October 1937, described camp SP-3-A in his book, The Ace In The Hole:

The road from Phoenix to South Mountain came through the campsite, separating the administrative offices from the rest of the buildings…it was imperative that the entire camp be ready for inspection at all times. This camp was the showplace for the Phoenix, District. All official guests who came to visit the Phoenix District headquarters were escorted to South Mountain and Camp SP-3-A.

For a C.C.C. company recently stationed in a remote camp near Grand Canyon, assignment to a camp so close to Phoenix was a welcome prospect, even if it meant the attention of visiting dignitaries, but high-ranking officials weren’t the only potential drop-in guests at the South Mountain camps. The 1936 Phoenix District Annual noted that Company 2860 and camp SP-4-A were “always on display and always ever ready for inspection by that most critical inspector, The Public…” South Mountain Park was already becoming a popular visitor attraction in part because of the work of the C.C.C. and the enrollees were expected to keep up appearances at all times.

The Tunnel That Almost Was

One project did not materialize, despite having the unqualified support of the landscape architect assigned to work on C.C.C. projects in the park. Department of the Interior plans called for a 500-foot long tunnel through the mountain near the summit of Telegraph Pass, linked to a southern approach road. In a 1936 letter to the Parks Department in Phoenix, William H. Douglass, the landscape architect who took credit for the tunnel idea, expressed satisfaction at hearing the tunnel was still being considered. Douglass explained that upon receiving word to halt construction of the tunnel road, he and the camp superintendent instead put the C.C.C. enrollees on overtime to excavate the site and, just before the camp was to close for the season, they set off charges, “so they [the next work crew] had to go ahead with the new location or leave a scar in the side of the mountain.” Despite Douglass’ best effort, the tunnel and its southern approach road were never completed, though the idea continues to crop up even today when residents living on the south side of the park demand better access to their jobs near downtown Phoenix.

A Fitting Legacy

By 1942 when the C.C.C. was disbanded South Mountain had 40 miles of trails, 18 buildings, 15 ramadas and 164 fire pits, water facets and other improvements largely due to the work of C.C.C. enrollees. Today, South Mountain Park no longer sits at the edge of the city, but is instead surrounded by homes and businesses, and little remains of the camps in which the Soil Soldiers lived and worked. However, the work of Roosevelt’s conservation army lives on in the ramadas and hiking shelters that continue to benefit visitors to South Mountain, and a careful hiker may even find a star-shaped stone and concrete structure that served as the base of the camp flagpole nearly 70 years ago. Copyright 2007. Michael Smith

(A modified version of this article previously appeared in the South Mountain Villager.)

Posted by

Michael

at

9:21 AM

3

comments

![]()

Labels: Arizona, Phoenix, South Mountain Park

Monday, July 9, 2007

Catching Up With Robert Moore: CCC Historian and Author

As we approach the 75th anniversary of the creation of the Civilian Conservation Corps, we expect that scholars and historians will increase their coverage and reporting of history related to the CCC - certainly that is our wish, anyway. A history of CCC work in Arizona promises to ride the wave of interest in this topic as we move closer to the important anniversary milestone in 2008. The Civilian Conservation Corps in Arizona’s Rim Country: Working in the Woods, by Robert J. Moore, published by the University of Nevada Press in 2006 will be of interest to anyone seeking a scholarly but down-to-earth account of CCC work in the western United States. Moore’s work includes footnotes, a useful bibliography, and index, which should make it a boon to other researchers of the CCC. On the other hand, the personal narratives make it historical storytelling at its best. Working in the Woods grew out of an exhibit Moore put together during his time as a seasonal ranger with the U.S. Forest Service in northern Arizona. After gathering a number of pictures of CCC work in Arizona for the exhibit, Moore decided it would make the foundation of a good book about the CCC. Work on the book began in the summer of 1999 and it was released for sale in August of 2006, but it wasn’t always an easy project. Moore estimates that he approached 15 to 20 publishers with his book proposal – amassing a good-sized stack of rejection letters – before the field of potential publishers was narrowed down to Texas A&M University Press and University of Nevada Press. In the end, the University of Nevada Press took on the project and the result is a terrific account of the work of the CCC in Arizona, a region Moore feels has been largely overlooked by CCC researchers and writers up to now.

Working in the Woods grew out of an exhibit Moore put together during his time as a seasonal ranger with the U.S. Forest Service in northern Arizona. After gathering a number of pictures of CCC work in Arizona for the exhibit, Moore decided it would make the foundation of a good book about the CCC. Work on the book began in the summer of 1999 and it was released for sale in August of 2006, but it wasn’t always an easy project. Moore estimates that he approached 15 to 20 publishers with his book proposal – amassing a good-sized stack of rejection letters – before the field of potential publishers was narrowed down to Texas A&M University Press and University of Nevada Press. In the end, the University of Nevada Press took on the project and the result is a terrific account of the work of the CCC in Arizona, a region Moore feels has been largely overlooked by CCC researchers and writers up to now.

Moore explains that the content of the book is divided roughly in half, with the first part of the book devoted to a history of approximately 13 Arizona camps, while the second half of the book is based upon interviews with CCC alumni, including Richard Thim, Eugene Gaddy, Charles Pflugh and Marshall Wood among others. Moore’s research centered primarily on camps in the Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest, but also includes information on camps in the Tonto and Coconino National Forests as well.

Moore expresses disappointment that more photographs could not be included in the book, but the publisher set a limit of 50 images, a rule that was strictly enforced despite Moore’s efforts to add additional pictures. In the end, Working in the Woods seems amply illustrated with a number of images that have seldom, if ever, been seen in Arizona and which certainly have been rarely viewed outside the state. Moore is also dismayed that the book isn’t being offered for sale in some Arizona locales that would seem to be an obvious fit, such as the Mogollon Rim Visitor Center in the Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest.

Moore said he has not been in constant contact with the publisher for updates on sales of the book but he reports orders have come in a “steady stream” and have come in from as far away as Hawaii. With the approach of the 75th anniversary of the CCC, it stands to reason

One advantage to having so much information for the book: Moore says that, because he was able to amass so much research material, he is planning to publish a CCC-related article in the Journal of Arizona History. Late word is that the piece will run in the issue due out in late July and will focus on the CCC experience of Pennsylvania enrollee Charles Pflugh and his CCC work at Chevalon Canyon, Arizona. Moore estimates that the Journal article will draw about 60% of its material from the book and 40% will be new material, along with about a dozen photos, most of which did not make it into the book and have never been published before.

Bitten by the CCC bug, Bob has begun another CCC research and writing project, this time focusing on CCC work in Wisconsin’s Devil’s Lake State Park where the CCC built trail and visitor amenities using native stone. Bob has been a friend to Arizona’s CCC alumni for a number of years and we’ve watched as he worked on and struggled with getting his book published. We continue to consider him a friend and even a member of our extended CCC family, but now, with the publication of The Civilian Conservation Corps in Arizona’s Rim Country: Working in the Woods, he will become a friend and family member to CCC alumni and researchers across the country.

Posted by

Michael

at

8:37 PM

5

comments

![]()

Labels: Arizona, Robert Moore, U.S. Forest Service

Saturday, July 7, 2007

The CCC and the German Labor Service: We Know The Difference

Despite what you may have heard, and contrary to what some historians may be saying in the months and years to come, our Civilian Conservation Corps and the Reich Labor Service of Nazi Germany were the offspring of two distinct ideologies and the programs approached their task from vastly different perspectives.

An in depth discussion and explanation of the CCC is not warranted here, except as it compares to its German counterpart but it may help to have a brief description of the German Reicharbeitsdeinst or RAD; the German National Work Service. The RAD was created in 1934 as the official labor service of the German state and the Nazi party. The RAD was an outgrowth of previous labor organizations that existed largely as a result of the economic hardships being faced by Germany in the 1920s and 1930s. In their initial manifestation, these labor organizations focused on supplying labor for agricultural related duties and relieving some of the strain of high unemployment – remember that the Great Depression was a worldwide depression and Germany likely suffered more as a result of her defeat in World War I. With the consolidation and renaming of various labor services over time, and the rise to power of the Nazis under the leadership of Adolf Hitler, six-month service in the newly named RAD became compulsory for young men aged 18 to 25. Upon completion of their RAD service, the young men then entered military service. (An exemption was given to young men who signed up for officer training, in which case their compulsory RAD service was waived.)

Knowing what we know, it’s difficult to understand how a historian or scholar could closely align the American CCC with the German RAD, but some have done it and in years to come, more may do so. Who knows why they’ll do it? They’ll do it because it’s fashionable to equate something noble with something sinister. They’ll do it to prove Franklin Roosevelt was a bum, or the New Deal a scam. They’ll do it because there’s nothing else to write about and they must publish something or risk losing their grant money, thereby slipping into that awful group of folks who have to work for a living.

Stated simply, we know the difference. Young Germans were compelled to join their nation’s labor service. Young men in America often begged to be allowed to enroll in the CCC and were occasionally turned away several times before gaining entry. In their first few weeks in the German National Work Service, young Germans learned military drill and the manual of arms (using a shovel instead of a rifle) before they ever set foot on a work site. In the United States, a distinct line was drawn between the work project and the limited influence of the military running the camps. Finally, no CCC enrollee embarked for combat against a foreign enemy and while many a former CCC enrollee earned a medal for valor, serving in some faraway place, he did so with his CCC service behind him and in the distinctly different uniform of the U.S. Marines, Army, Navy, Coast Guard or Merchant Marine – not in the forest green uniform of the CCC.

Posted by

Michael

at

2:54 PM

3

comments

![]()

Labels: Germany, RAD, Reicharbeitsdeinst, World War II

Thursday, July 5, 2007

Soldier, Statesman, CCC Commander

George C. Marshall, the only soldier to receive the Nobel Peace Prize, was a Civilian Conservation Corps commander in the northwest United States before rising to prominence during World War II and its aftermath.

Of his association with the CCC, Marshall recalled: "I found the CCC the most instructive service I have ever had, and the most interesting. The results one could obtain were amazing and highly satisfying…" And, "a splendid experience for the War Department and the army…best antidote for mental stagnation that an Army officer in my position can have."

Marshall, who lived in Vancouver, Washington from 1936 to 1938, was commander of the Vancouver Barracks where he was also charged with the task of setting up 19 camps and supervising 35 more. Marshall went on to become a five-star General of the Army, chief of staff and finally secretary of state where he authored the famous Marshall Plan for rebuilding Europe following its destruction during World War II. Marshall was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1953.

Here’s a telling incident from the book Soldier, Statesman, Peacemaker by Jack Uldrich:

A brash young major stormed into Marshall’s office and said, “I’m a graduate of West Point. I’m not going to come down here and deal with a whole lot of bums…[and] half-dead crackers.” The major assumed that Marshall would cave in to his demand for transfer out of the CCC. Marshall replied, “Major, I’m sorry you feel like that. But I’ll tell you this-you can’t resign quick enough to suit me.” As the young major stood there stunned, Marshall added, “Now get out of here!”

Posted by

Michael

at

6:50 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Army, CCC, Civilian Conservation Corps, George Marshall

Tuesday, July 3, 2007

A Peaceful Occupation: The C.C.C. Remembered

In 1933 a conservation army trooped into the forests, fields and parks of this country to begin what would ultimately amount to some nine years of continuous work. The conservation army that undertook this peaceful occupation was Franklin Roosevelt’s Civilian Conservation Corps- the CCC. Among the results: trail systems in Grand Canyon, visitor amenities in Yellowstone, Shenandoah, and Acadia, improvements at Mesa Verde, Colossal Cave, and Colorado National Monument and forestry improvements in all of our national forests. And this only scratches the surface.

Historians and economists are mixed in their appraisals of FDR’s Depression-era New Deal. Some argue the many alphabet agencies created under the New Deal were a lifesaver to millions of Americans, while others point to the creation of so many government agencies and mark it as the rise of bigger government and the demise of personal self-sufficiency in our culture. Some experts have even argued that Roosevelt’s policies actually prolonged the Great Depression. My point here is not to argue the merits of the New Deal at large. I’m not an economist. I will never attempt to defend so large and grandiose an endeavor as the New Deal, but I’ll defend the record of the CCC against all comers. And I believe I can say without fear of contradiction that the Civilian Conservation Corps was the most successful, most popular and most fondly remembered of all New Deal programs.

The Emergency Conservation Work program, as the CCC was originally called, was part of Roosevelt’s first 100 days in office. From the time that it was initially introduced, the act that created the CCC took just eighteen days to get through congress and on March 31, 1933 President Roosevelt signed the bill into law. The measure under which the CCC was created was known simply as “an act for the relief of unemployment through the performance of useful public work.” There were no grandiose proclamations about saving the environment just the promise of gainful employment for single young men aged 17 to 28 years. Roosevelt hoped to avoid drawing workers out of the nation’s farms, fields and factories by focusing the effort on conservation. Roosevelt explained, “I propose to create a civilian conservation corps to be used in simple work, not interfering with the normal employment, and confining itself to forestry, the prevention of soil erosion, flood control, and similar projects…This enterprise will…conserve our precious natural resources. It will pay dividends to present and future generations. More important, however, than the material gains will be the moral and spiritual gains of such work.”[Emphasis added.] Roosevelt was referring to the “overwhelming majority of unemployed Americans…[who]…would infinitely prefer to work,” and perhaps more specifically to a vast army of unemployed youth who’d taken to the roads and rails in search of employment.

Roosevelt’s stated goal was to have 250,000 young men deployed to forestry camps across the nation by the spring of 1933. The goal seemed unattainable, but enthusiasm at the local level was immense. Within two weeks of the official creation of the CCC, Montana, Wyoming, Colorado and New Mexico informed the administration that 23,480 idle workers could be put to work in their states immediately. This figure applied to workers for national forest lands only; additional workers were needed for projects on state land and in National Parks as well.

In a cooperative effort not seen before or since, the Departments of War, Labor, Agriculture, and the Interior, worked together to select suitable enrollees, provide the necessary medical checks and inoculations, issue supplies and work clothes and arrange transportation to the many camps scattered throughout the United States and its territories. Contrary to some notions, the CCC was not run by the military. The camps – usually home to about 200 enrollees – were placed under the command of a reserve military officer, but military discipline was prohibited and enrollees were only under general control of the commanding officer during their hours in camp. During the workday, enrollees labored and learned under the watchful eye of foremen and supervisors from the technical services such as the Forest Service, National Park Service, Bureau of Reclamation and the Soil Conservation Service.

Roosevelt’s initial enrollment goal was achieved and ultimately some 3 million young men passed through the ranks of the CCC between 1933 and 1942. For their six month enrollment, enrollees were housed, clothed, fed and paid $30 a month, of which as much as $25 was sent home to needy family members; after all, what good was $30 in the pocket of a lad living in a forest camp? What the economy needed was dollars to circulate and the CCC helped make that happen. The establishment of a CCC camp typically meant an additional $5,000 in monthly expenditures in the local marketplace. Some camp commanders, sensing that the presence of their camp was not fully appreciated by the local populace, used silver dollars to pay the enrollees their $5 monthly allowance, which was often quickly spent in the local town. Merchants, suddenly finding so many silver dollars in their cash registers, would quickly realize what a boon the nearby camp had become.

Nationwide, the work of the CCC is staggering even today. At civil war battlefields monuments were repaired and cleaned and the unheralded dead exhumed to be carefully placed in cemeteries. In our nation’s dust bowl region CCC enrollees worked on erosion control projects and shelterbelts. West of Denver, in a natural bowl of huge flanking red rock formations, CCC crews built Red Rocks Park and Amphitheater to take advantage of the natural acoustics in the magnificent geologic feature. The amphitheater continues to draw concertgoers today. In the Carolinas, young men worked with archaeologists researching prehistoric cultures. At the Mission La Purisima, a mission church originally constructed in the late 1700s in what is today Lompoc, California, enrollees were put to work rebuilding the ancient mission using largely the same tools and techniques used during the original construction. Young men worked redwood roof timbers with adze and axe. Other enrollees painstakingly recreated the proper texture on the exterior adobe. In a wood shop enrollees worked on reconstructing everything from the mission’s massive doors to handmade replicas of mission furniture. Indeed, the quest for authenticity was so strict that even ironwork like locks, keys, hinges, iron and brass lighting fixtures and iron nails were hand-forged.

Still other chores cropped up out of immediate necessity; for example, the use of CCC personnel to fight forest fires is a widely documented practice and several enrollees gave their lives in this effort. Search and rescue operations frequently took advantage of CCC manpower and enrollees gathered ticks for scientists studying Rocky Mountain spotted fever. All in a day’s work, an enrollee might learn how to sharpen tools, work in concrete and masonry, operate a jackhammer, set explosives or drive a caterpillar tractor.

In fiscal year 1937 alone the CCC built a total of 2,476 vehicle bridges, 11,559 miles of truck trails and they strung over 10,000 miles of telephone and power lines, largely to the benefit of our National Forests and National Parks. Multiplied over 9 years, these sorts of numbers become almost incomprehensible and the fact that we continue to derive benefit from this work almost three-quarters of a century later is unfathomable in our modern throwaway society.

In addition to gaining work skills training, many CCC enrollees were given an opportunity to continue their grade school and high school education, and some progressed to college level coursework by attending classes in the evenings. Additionally, a significant short-term benefit came out of the CCC program that has not been widely explored by historians. Experience in the CCC camps prepared many young men for their coming service in the military during World War II. Accustomed to some form of discipline and regimentation, knowledgeable in the rudiments of keeping their living quarters squared away, the former CCC enrollee-turned-GI Joe could get on with the more important tasks of training for combat. So, while many decried its quasi-military structure during the 1930s, many others would see the CCC as having been a valuable breaking-in period for the much rougher years from 1942 to 1945.

America’s entry into World War II following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 signaled the end of the CCC. Faced with a two-front war, and with America’s industrial complex gearing up for the war effort, congress failed to appropriate funds to keep the CCC working in the forests, fields and parks, and by the end of fiscal year 1943 the program was deemed fully liquidated. The “boys” of the CCC became the men of Corregidor, Midway, Anzio and Omaha Beach. Vocational skills gained in the CCC camps were put to use in our factories building tanks and airplanes. Nearly to a man, former CCC enrollees will tell you that the CCC was the best thing that ever happened to them, but as a nation we tend to remember more about the World War they fought between 1942 and 1945, than we do the quieter time from 1933 to 1942 when our nation was home to the Civilian Conservation Corps and its peaceful occupation. copyright 2007 Michael I. Smith

Posted by

Michael

at

1:55 PM

0

comments

![]()

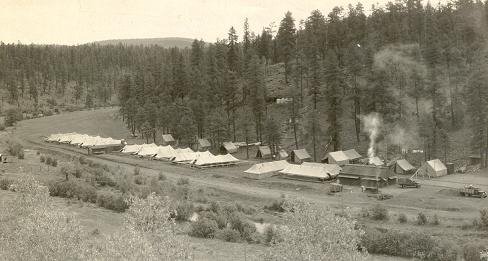

Buffalo Crossing Camp, Eastern Arizona