A photograph of 19 flag-draped body

bags lying in the burn area emerged in the days immediately following the

Yarnell Hill tragedy and in short order there has been debate regarding whether

such an image is appropriate and whether it might be too intrusive. While I rarely editorialize here, I will say

in this case, that the sad image of 19 flag-draped forms is a fitting eulogy to

young men who gave up their very existence in the fight against wildland

fire. I only wish things had been the

same 75 years ago when flames overtook the CCC crews at Blackwater; however in

their case, there were no flags, only canvas.

I’ve chosen not to post the final

image of the Yarnell Hill 19 lying near where they likely fell but anyone with

an ounce of internet savvy will be able to find it. On the other hand, I am posting a picture

from the 1937 Blackwater Creek tragedy with the hope that it will generate some

thought regarding how much things have changed in 75 years of forestry,

firefighting and humanity.

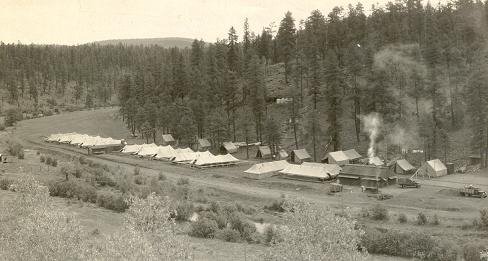

In the hours immediately after the 1937

Blackwater blow up and its tragic consequences, fire suppression work all but

ceased as crews fanned out into the burn to search for victims. Most of the dead were discovered in the

process of extricating another group – the living, the dead and dying – who had

been trapped by the blow up. With help

from rescue parties, the scarred and fatigued survivors carried the dead and

dying down to the lower fire camps where they were tended to before being transported

to hospitals in Cody, Wyoming.

It strikes me that retrieval of the

dead in cases like the Yarnell Hill Fire, as with other recent tragedies that

have preceded it, must be undertaken as a mix of requiem and a search for

investigative clarity. There are honors

to be rendered but also questions to be answered. The impulse to mourn will be interrupted, abruptly

and perhaps grudgingly, by the desire to find answers, to learn lessons and

perhaps even assess blame. I do not get

the impression that such was the case 75 years ago on the fire scarred

hillsides of a forest near Yellowstone National Park. The body of Ranger Al Clayton and the six men

who died with him were removed in the late morning and early afternoon of

August 22, 1937 and a local newspaper reporter wrote of the scene:

Seven pack-horses, each with angular forms

wrapped in canvas and lashed to the saddles, filed slowly out of the wooded

ravine and stopped at the cars. Over a

hundred wide-eyed, ashen-gray youngsters, just ready to go to the fire line,

pushed forward, drawn by a chilling magnetism to see what their former comrades

looked like.

No flag-draped body bags, no honor

guard processions, just canvas wrapped parcels somewhat ghoulishly exhibited

for all to see in a grim processional.

In the midst of the death and fear – in spite of the death and fear - fresh

CCC crews continued to arrive until at one point more than 500 men were

fighting the Blackwater Fire. By noon on

Tuesday, August 24th the fire was listed as officially under control and on the

following day the Forest Service supervisors began to release CCC crews to

return to their camps and their regular duties.

Finally, on August 31st, ten days after the fatal blow up and almost two

weeks after lightening started a seemingly inconsequential blaze, the last of

the firefighting crews were disbanded, having constructed more than eleven

miles of fire line in the process of extinguishing the Blackwater Fire.

Photos of the recovery of the

Blackwater victims appeared in the August 1941 issue of Sports Afield and perhaps elsewhere and I am unaware of any

backlash at the time. Perhaps the

passage of four years’ time helped dull the impact. Perhaps the amnesia had already begun to set

in by that point. Perhaps the growing

global carnage diminished Blackwater’s fiery cataclysm down to seemingly

nothing by comparison. Perhaps people

simply had thicker skins 75 years ago.

I have argued that the dead of

Blackwater have not received the same sort of recognition as their firefighting

brethren who have perished on the fire lines in recent memory, but one thing

seems constant over the decades. Praised

or unsung, the heroes have done their work and perished in the doing. The dismal grim business remains for us, the

living, to undertake and sadly that business won’t be quick or clean.

You can read an earlier, more detailed post about the Blackwater

tragedy here.

©Michael I. Smith, 2013