A Forest Army Post in Honor of Black History Month

If the Civilian Conservation Corps had one failing, it would have to be in the area of racial integration and equality. Although the legislation that created the CCC included language expressly forbidding discrimination on the basis of race, problems cropped up almost immediately during the initial selection process in the individual states and continued throughout the life of the program. Looking back it seems clear that there was blame to go around; President Roosevelt was reluctant to use the New Deal as a platform to promote the sort of strong social agenda represented by integration, CCC Director Robert Fechner, as a southerner, was pre-disposed to notions favoring Jim Crow, some military officers were opposed to integration if not opposed to black enrollment altogether and finally, nationwide, communities large and small came out in opposition to the establishment of all-black CCC camps. And yet looking back there are exceptions to these notions and also reasons to be glad for the opportunity the CCC provided to young black men at perhaps our nation’s bleakest time and to view that opportunity for what it was: a small step toward future successes.

If the Civilian Conservation Corps had one failing, it would have to be in the area of racial integration and equality. Although the legislation that created the CCC included language expressly forbidding discrimination on the basis of race, problems cropped up almost immediately during the initial selection process in the individual states and continued throughout the life of the program. Looking back it seems clear that there was blame to go around; President Roosevelt was reluctant to use the New Deal as a platform to promote the sort of strong social agenda represented by integration, CCC Director Robert Fechner, as a southerner, was pre-disposed to notions favoring Jim Crow, some military officers were opposed to integration if not opposed to black enrollment altogether and finally, nationwide, communities large and small came out in opposition to the establishment of all-black CCC camps. And yet looking back there are exceptions to these notions and also reasons to be glad for the opportunity the CCC provided to young black men at perhaps our nation’s bleakest time and to view that opportunity for what it was: a small step toward future successes.For excellent accounts of the initial problems and indeed a valuable discussion of the problem of racism in the CCC throughout its lifespan, two books immediately come to mind: John Salmond’s groundbreaking work from the 1960s, The Civilian Conservation Corps, 1933-1942: A New Deal Case Study and Joseph Speakman’s more recent book At Work in Penn’s Woods: The Civilian Conservation Corps in Pennsylvania. Both books devote an entire chapter to the issue of race and racism in the CCC; Salmond in a chapter titled “The Selection of Negroes, 1933-1937,” and Speakman in a chapter titled “African-Americans in Penn’s Woods. (A copy of Salmond’s important work is now available online and can be viewed here. For an earlier Forest Army review of At Work in Penn’s Woods click here.)

Speakman describes the life of black CCC enrollees as an existence in a parallel universe, in an organization similar to the CCC but called the “Colored Civilian Conservation Corps” – the CCCC. Speakman notes that approximately 250,000 black enrollees served in the CCC between 1933 and 1942 but he questions whether black enrollment would have been much different had Republican Representative Oscar De Priest (an African-American congressman from Illinois) not fought to have the non-discrimination amendment added to the legislation creating the Emergency Conservation Work program. As Speakman himself acknowledges, it is impossible to say what the alternative might have been had De Priest’s amendment not been made.

Speakman describes the life of black CCC enrollees as an existence in a parallel universe, in an organization similar to the CCC but called the “Colored Civilian Conservation Corps” – the CCCC. Speakman notes that approximately 250,000 black enrollees served in the CCC between 1933 and 1942 but he questions whether black enrollment would have been much different had Republican Representative Oscar De Priest (an African-American congressman from Illinois) not fought to have the non-discrimination amendment added to the legislation creating the Emergency Conservation Work program. As Speakman himself acknowledges, it is impossible to say what the alternative might have been had De Priest’s amendment not been made.For his part, Salmond doesn’t delve too deeply into the what-ifs of diversity and racial integration in the CCC, however both he and Speakman cite an account from one black enrollee that is especially significant and insightful.

Meeting Jim Crow at Camp Dix

The black enrollee whom Salmond and Speakman quote is Luther C. Wandall and his comments appeared in the August 1935 issue of Crisis. Young Luther Wandall wrote at length about his experience in the CCC, from initial enrollment to camp life experiences. Wandall’s experience at Camp Dix is especially noteworthy as a glimpse not simply of how whites of the time treated blacks as a simple matter of policy but also how blacks viewed whites. Part of Wandall’s experience, under the heading “Jim Crow at Camp Dix,” merits an extensive quote:

The black enrollee whom Salmond and Speakman quote is Luther C. Wandall and his comments appeared in the August 1935 issue of Crisis. Young Luther Wandall wrote at length about his experience in the CCC, from initial enrollment to camp life experiences. Wandall’s experience at Camp Dix is especially noteworthy as a glimpse not simply of how whites of the time treated blacks as a simple matter of policy but also how blacks viewed whites. Part of Wandall’s experience, under the heading “Jim Crow at Camp Dix,” merits an extensive quote:We reached Camp Dix about 7:30 that evening. As we rolled up in front of headquarters an officer came out to the bus and told us: “You will double-time as you leave this bus, remove your hat when you hit the door, and when you are asked questions, answer ‘Yes, sir,’ and ‘No, sir.’”

And here it was that Mr. James Crow first definitely put in his appearance. When my record was taken at Pier I, a “C” was placed on it. When the busloads were made up at Whitehall Street an officer reported as follows: “35, 8 colored.” But until now there had been no distinction made.

But before we left the bus the officer shouted emphatically: “Colored boys fall out in the rear.” The colored from several buses were herded together, and stood in line until after the white boys had been registered and taken to their tents. This seemed to be the established order of procedure at Camp Dix.

This separation of the colored from the whites was completely and rigidly maintained at this camp. One Puerto Rican, who was darker than I, and who preferred to be with the colored, was regarded as pitifully uninformed by the officers.

While we stood in line there, as well as afterwards, I was interested to observe these officers. They were contradictory, and by no means simple or uniform in type. Many of them were southerners, how many I could not tell. Out of their official character they were usually courteous, kindly, refined, and even intimate. They offered extra money to any of us who could sing or dance. On the other hand, some were vicious and ill-tempered, and apparently restrained only by fear.

So you can imagine my feelings when an officer, a small quiet fellow, obviously a southerner, asked me how I would like to stay in Camp Dix permanently as his clerk! This officer was very courteous, and seemed to be used to colored people, and liked them. I declined his offer.

And here it was that Mr. James Crow first definitely put in his appearance. When my record was taken at Pier I, a “C” was placed on it. When the busloads were made up at Whitehall Street an officer reported as follows: “35, 8 colored.” But until now there had been no distinction made.

But before we left the bus the officer shouted emphatically: “Colored boys fall out in the rear.” The colored from several buses were herded together, and stood in line until after the white boys had been registered and taken to their tents. This seemed to be the established order of procedure at Camp Dix.

This separation of the colored from the whites was completely and rigidly maintained at this camp. One Puerto Rican, who was darker than I, and who preferred to be with the colored, was regarded as pitifully uninformed by the officers.

While we stood in line there, as well as afterwards, I was interested to observe these officers. They were contradictory, and by no means simple or uniform in type. Many of them were southerners, how many I could not tell. Out of their official character they were usually courteous, kindly, refined, and even intimate. They offered extra money to any of us who could sing or dance. On the other hand, some were vicious and ill-tempered, and apparently restrained only by fear.

So you can imagine my feelings when an officer, a small quiet fellow, obviously a southerner, asked me how I would like to stay in Camp Dix permanently as his clerk! This officer was very courteous, and seemed to be used to colored people, and liked them. I declined his offer.

Local Actions and Reactions, Good and Bad

Local Actions and Reactions, Good and BadWhen it came to honoring the no discrimination clause of the CCC act, individual states often had to be dragged kicking and screaming into the right. For example, regarding Arkansas’s CCC enrollment selection process, Salmond wrote of an exchange that took place between Director of CCC enrollment Frank W. Persons and Arkansas’s relief director William Rooksbery in 1933:

Similarly (compared to Georgia), after investigating an NAACP complaint of discrimination in Arkansas, Persons again threatened to withhold quotas. The state’s indignant relief director, William A. Rooksbery, unequivocally denied the charge that no Negroes had been selected. No less than three had in fact been enrolled, he protested, but Persons was unimpressed, and told him so. The chastened state official promised to induct more within the following few weeks.

And yet it seems that in some cases, the farther down the chain of authority we travel, the more receptive and open minded the parties became. Harley E. Jolley, writing in, That Magnificent Army of Youth and Peace: The Civilian Conservation Corps in North Carolina, 1933-1942, notes that officials at the county level often implored the state recruiting offices to increase their quota of black enrollees. For example, this appeal: “Hoke County’s case load more than half colored. Please advise if possible to change part of the white quota to colored.” And from Orange County: “If there is anything you can do toward allowing for a considerable number of negroes instead of white men it would certainly help out our local relief situation.” But Jolley goes on to point out that, “Invariably, however, the state CCC administrator summarily rejected such requests…”

Often, the local request for black enrollees came in the form of an awkward and easily identified backhand compliment that rings with cultural insensitivity today. Jolley recounts the editor of a local paper in Shelby, North Carolina, who wrote in support of an all black CCC camp being established nearby: “In the first place, the work to be done here is precisely the kind of work that negroes do better than white men. It will be ditch digging, terracing, and drainage work, with picks and hoes, and shovels. A gang of negroes…can do that kind of work better and happier than any other crew. In the second place, the colored boys are more tractable.” Later, an army engineer affiliated with the construction of the camp was quoted as saying, “Why, we have been controlling negroes in the south for more than 400 years. As a matter of fact, most of the progress of the Southland has been built on the broad shoulders of black boys just like these. They’ll be no problem to the city at all, whereas white boys often are.”

No question but the issue of race in the CCC was most significant in the south. In a region of the country where blacks made up as much as 50 percent of the total population, the lack of recruitment of blacks for work in southern CCC camps is disgusting today, but must be viewed in light of the overriding system of prejudice at the time. Further, cases of racism were not confined to the southern states by any means and looking back we find that camps were segregated by race nationwide and that all-black camps ran into local opposition in such seemingly progressive regions as California.

No question but the issue of race in the CCC was most significant in the south. In a region of the country where blacks made up as much as 50 percent of the total population, the lack of recruitment of blacks for work in southern CCC camps is disgusting today, but must be viewed in light of the overriding system of prejudice at the time. Further, cases of racism were not confined to the southern states by any means and looking back we find that camps were segregated by race nationwide and that all-black camps ran into local opposition in such seemingly progressive regions as California.The January 13, 1934 issue of the Norfolk Journal and Guide reported that in September 1933 Eddie Simons, a young black enrollee, was given a dishonorable discharge on the spot and denied his last months pay when he refused to fan the flies off of a young lieutenant from the 16th Infantry, temporarily in command of a CCC camp in North Lisbon, New Jersey. After the NAACP took up young Simons’ cause and protested the injustice to no less a person than Robert Fechner, the enrollee was given an honorable discharge “free from any charge of insubordination” and paid what he was owed.

Salmond points out that, beyond the initial difficulty of actually getting young blacks selected and enrolled into the CCC, Arkansas citizens “accepted with equanimity many Negro camps…” while at places like Contra Costa County, California, members of the community noted that black enrollees assigned to a local camp were frequently, “in an intoxicated condition,” and claimed that the camp was “a menace to the peace and quiet of the community.” Likely as a result of this nationwide bias, CCC Director Robert Fechner never forced the issue and, if local protests erupted due to the all-black composition of a CCC camp, he would order the camp closed or moved onto an Army reservation, for, as both Salmond and Speakman point out, in Fechner’s own words, Fechner was “a Southerner by birth and raising” and thus he, “clearly understood the Negro problem.”

Fechner’s “Problem”

And yet it seems unclear whether Fechner did truly understand the “negro problem,” given that he insisted CCC companies be segregated by race and he seems to have been opposed to appointing blacks as supervisors in segregated, all-black CCC camps. Fechner clearly didn’t understand the “problem” from the point of view of the “negro” enrollee; perhaps Fechner simply thought of Negroes as a problem, best avoided and at least kept separate.

And yet it seems unclear whether Fechner did truly understand the “negro problem,” given that he insisted CCC companies be segregated by race and he seems to have been opposed to appointing blacks as supervisors in segregated, all-black CCC camps. Fechner clearly didn’t understand the “problem” from the point of view of the “negro” enrollee; perhaps Fechner simply thought of Negroes as a problem, best avoided and at least kept separate.In his book Parks for Texas: Enduring Landscapes of the New Deal, historian James Wright Steely casts a light on what is perhaps the precise moment that Fechner decreed that CCC companies be segregated by race. In 1935 when local officials in Texas advocated keeping integrated CCC camps as a compromise – indeed as an alternative – to newly proposed all-black companies, Fechner was pushed “over the edge,” as Steely points out:

“It is astonishing to me that…Mr. Colp would suggest that white and colored Texas boys be enrolled in the same Civilian Conservation Corps company and domiciled in the same camp…Every negro enrollee in Texas is a Texas negro. No out of state negroes are sent into Texas and in conformity with that practice no Texas negroes will be sent to any other state.”

And thus the rules were established, the segregationist policy applied to camps in every state and territory, with the required camp and company reorganizations commencing immediately. And yet we occasionally get a glimpse of the task that Fechner had before him – notwithstanding his own racial prejudices – for he clearly understood the useful work that could be accomplished by CCC companies of any race and when faced with local opposition to all-black CCC camps, Fechner would bend to local pressure but not before reminding the locals what they might be missing. James Steely recounts Fechner’s response to the local populace following the redeployment of an all-black CCC camp from Goose Island State Park to Fort Sam Houston after it ran into local opposition. Fechner later explained to local officials: “We do not endeavor to force any community to accept a Civilian Conservation Corps company against its will, however we have to find a location for these negro companies and failing to work out the problem in a satisfactory manner…the War Department has always expressed its willingness to accept a negro company and place it on an Army reservation. Where this is done it means, of course, that the state loses an approved Civilian Conservation Corps camp.” [Emphasis added.] One can almost hear Fechner’s whispered, “It’s your loss,” nearly 80 years later.

Fechner will be viewed as no less close-minded with respect to appointing black supervisors in those all-black CCC companies that were as much a product of his personal preferences as any one else’s. In a letter dated September 26, 1935, Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes wrote to Fechner:

I have your letter of September 24 in which you express doubt as to the advisability of appointing Negro supervisory personnel in Negro CCC camps. For my part, I am quite certain that Negroes can function in supervisory capacities just as efficiently as can white men and I do not think that they should be discriminated against merely on account of their color. I can see no menace to the program that you are so efficiently carrying out in giving just and proper recognition to members of the negro race.”

Robert Fechner was a product of his time and a man caught in the middle. Today it seems clear that Roosevelt appointed Fechner as a sop to southern states – in an effort to get the south to support his New Deal agenda. Once appointed, Fechner, whose own father had fought for the Confederacy and lost a leg as a result, seems to have been caught between a traditional loyalty to the old Jim Crow ways of his native south, and the burgeoning egalitarianism beginning to blossom in the United States. Sadly for Fechner, he happened to be put in charge of the one New Deal program best suited for taking bold steps in the area of racial equality. In hindsight, we should be thankful Fechner did as much as he did in this regard given his background and the tenor of the times. Indeed, James Steely points out yet another bitter bit of irony in the fact that black enrollees frequently worked on park and forest improvements that would ultimately be barred to African-American citizens under local Jim Crow laws and history will record that Robert Fechner had nothing whatsoever to do with how the parks were used once the CCC boys finished their work; the blame for that injustice falls at the feet of others.

Robert Fechner was a product of his time and a man caught in the middle. Today it seems clear that Roosevelt appointed Fechner as a sop to southern states – in an effort to get the south to support his New Deal agenda. Once appointed, Fechner, whose own father had fought for the Confederacy and lost a leg as a result, seems to have been caught between a traditional loyalty to the old Jim Crow ways of his native south, and the burgeoning egalitarianism beginning to blossom in the United States. Sadly for Fechner, he happened to be put in charge of the one New Deal program best suited for taking bold steps in the area of racial equality. In hindsight, we should be thankful Fechner did as much as he did in this regard given his background and the tenor of the times. Indeed, James Steely points out yet another bitter bit of irony in the fact that black enrollees frequently worked on park and forest improvements that would ultimately be barred to African-American citizens under local Jim Crow laws and history will record that Robert Fechner had nothing whatsoever to do with how the parks were used once the CCC boys finished their work; the blame for that injustice falls at the feet of others.

Elsewhere, Occasional Integration

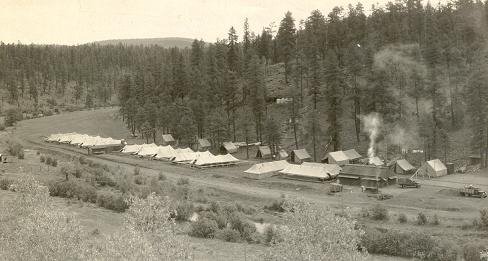

Elsewhere, Occasional IntegrationNaturally, in southern states, CCC camps were strictly segregated, however there were instances of integrated CCC camps elsewhere in the United States. For example, in Arizona, where the percentage of black residents was very small, there were not enough minority enrollees to create segregated CCC companies so young black men were simply enrolled into existing CCC companies. Speakman points out that the existence of even these few integrated camps annoyed Fechner, and yet, exist they did and generally with meaningful success.

The story of a black enrollee called “Old Joe,” offers a useful glimpse of how race relations were often smoothed over naturally in an integrated camp setting. Writing in the book Iron Mike: The Life of General Ernest L. Massad, James C. Milligan recounts the seemingly sad story of a black enrollee at a CCC camp in Sedona, Arizona. The enrollee, whom everyone called “Old Joe” was reportedly mentally retarded and likely should not have been admitted to the CCC on those grounds alone, but enrolled he was and assigned along with two other black enrollees to the Sedona camp. Unfortunately, Old Joe was being tormented by white enrollees who were deliberately scaring him at night. Old Joe went to then Lieutenant Massad and said, “Lieutenant, they’re going to kill me.” Lieutenant Massad soothed the frazzled enrollee’s nerves as best he could but it was an incident out in the field that eventually resolved the touchy racial situation. A group of enrollees were erecting a line of telephone poles along a roadside and were struggling with a particularly heavy one. Watching as four enrollees labored with the cumbersome telephone pole, Old Joe grew increasingly impatient until he finally pushed the struggling crew aside and, grabbing the bulky pole, single-handedly muscled the monster into the ground. Reportedly, from that point on all three black enrollees were treated as equals and Old Joe’s tormenters left him alone. With regard to race, Milligan quotes Massad as saying: “When they [the three black enrollees] showed up, I had too much military in me; I had no prejudice at all. The boys all looked the same to me, and they were treated just like everybody else. If they got into trouble they were treated just like the others.”

Perhaps Arizona – situated as it is, west of – rather than north or south of - the Mason-Dixon line – was better suited for more than a fair share of pre-integration experimentation during the 1930s. In his forthcoming book, Shaping the Park and Saving the Boys: The Civilian Conservation Corps at Grand Canyon, 1933-1942, scheduled for publication in 2012, historian

Bob Audretsch relates the story of John B. Scott, a black CCC enrollee who worked right alongside white enrollees at Grand Canyon. Indeed, Scott, who hailed from Spur, Texas, was so well respected that he was assigned the task of monitoring new enrollees on the work site and his diligence saved the life of at least one new enrollee (but you’ll have to wait for the Audretsch book to come out to learn the details). One detail of John Scott’s service in the CCC is striking and that is the fact that if he was indeed from Texas (as is indicated in the 1936 Phoenix District Annual) it means his case represents a situation where a black enrollee was working outside of his home state in a CCC camp in another state, in the same Corps area, after Fechner’s 1935 directive that blacks be placed in camps within their home states.

Bob Audretsch relates the story of John B. Scott, a black CCC enrollee who worked right alongside white enrollees at Grand Canyon. Indeed, Scott, who hailed from Spur, Texas, was so well respected that he was assigned the task of monitoring new enrollees on the work site and his diligence saved the life of at least one new enrollee (but you’ll have to wait for the Audretsch book to come out to learn the details). One detail of John Scott’s service in the CCC is striking and that is the fact that if he was indeed from Texas (as is indicated in the 1936 Phoenix District Annual) it means his case represents a situation where a black enrollee was working outside of his home state in a CCC camp in another state, in the same Corps area, after Fechner’s 1935 directive that blacks be placed in camps within their home states.Despite Fechner’s reluctance, or outright opposition to putting blacks in positions of authority in CCC camps, some blacks did indeed rise to supervisory positions in the all-black CCC camps. Indeed, black reserve officers were even assigned to camps as medical officers and chaplains. In Pennsylvania, Captain Frederick Lyman Slade became the first black officer to command an all-black CCC camp when he assumed command duties at Camp MP-2 in Gettysburg in August of 1936 and by 1938, according to Speakman, all the military officers, including the medical officer as well as the educational advisor at the Gettysburg camp were African-American. But sadly, the ascendancy of minority representation came at the same time as the number of all-black camps was dwindling and black officers were placed in charge of only one other CCC camp before the program was disbanded.

The Cold Hard Truth In Black and White

The Cold Hard Truth In Black and WhitePerhaps three vignettes of life in the CCC – literally illustrated - will serve to exemplify what black enrollees faced during their time in the Civilian Conservation Corps. The Arkansas Gazette Magazine of Sunday, February 18, 1934, included a very complimentary article entitled “Arkansas’s Negro CCC Camp.” Buried low in the first column of text, under the heading Late One Scene is the following:

Having been opened many months after the 38 CCC camps for whites began functioning, this CCC for Negroes got lost in the shuffle, as it were, so far as newspaper notice was concerned. Consequently Camp P-58 has hitherto received no publicity whatever in daily or weekly newspapers of Arkansas, possibly proving that both the whites and the Negroes in this camp, notwithstanding evident personal pride in achievements, posses rather rare modesty.

Given what we now know about the reluctance of Arkansas officials to enroll black enrollees into the CCC, is it any wonder this camp was “late on the scene”? Remember that by about July 1933, Arkansas had only enrolled 3 black enrollees. Yet the press easily smoothed over this chronological discrepancy.

Included in the illustrations for historian Robert Moore’s outstanding book The Civilian Conservation Corps in Arizona’s Rim Country is a detail of a group photo of Company 864 assigned to Camp F24-A at Arizona’s Bar X Ranch. The casual observer will be gratified to see that there are nine black enrollees in this integrated CCC company, but gratification turns to dismay when one realizes that the nine black enrollees are sitting well apart from the rest of the company. (Elsewhere, I have seen company photos in which a chalk outline has been made on the ground to direct the black enrollees exactly where to sit!)

A final sobering illustration of how the races were separated in the CCC can be found in the 1935 Official Annual of District ‘E’ Fourth Corps Area. Thumbing through this 232-page book is an enjoyable look at the history and work of the CCC in Louisiana and Mississippi and it all seems like a wonderful account of hard work and lives changed until you realize that the book itself is segregated into a white and black section, separated by a blank Certificate of Enrollment form. The histories of the all-black companies are, in keeping with the standards of the day, in the back of the book, separated from the histories of the all white companies by a blank certificate of enrollment form, included almost as an afterthought.

Given what we now know about the reluctance of Arkansas officials to enroll black enrollees into the CCC, is it any wonder this camp was “late on the scene”? Remember that by about July 1933, Arkansas had only enrolled 3 black enrollees. Yet the press easily smoothed over this chronological discrepancy.

Included in the illustrations for historian Robert Moore’s outstanding book The Civilian Conservation Corps in Arizona’s Rim Country is a detail of a group photo of Company 864 assigned to Camp F24-A at Arizona’s Bar X Ranch. The casual observer will be gratified to see that there are nine black enrollees in this integrated CCC company, but gratification turns to dismay when one realizes that the nine black enrollees are sitting well apart from the rest of the company. (Elsewhere, I have seen company photos in which a chalk outline has been made on the ground to direct the black enrollees exactly where to sit!)

A final sobering illustration of how the races were separated in the CCC can be found in the 1935 Official Annual of District ‘E’ Fourth Corps Area. Thumbing through this 232-page book is an enjoyable look at the history and work of the CCC in Louisiana and Mississippi and it all seems like a wonderful account of hard work and lives changed until you realize that the book itself is segregated into a white and black section, separated by a blank Certificate of Enrollment form. The histories of the all-black companies are, in keeping with the standards of the day, in the back of the book, separated from the histories of the all white companies by a blank certificate of enrollment form, included almost as an afterthought.

A Blurred Conclusion, Perhaps

A Blurred Conclusion, PerhapsWith respect to the treatment of minorities in the CCC, Salmond wrote:

The outcome of the controversy over Negro enrolment is an obvious blot on the record of the CCC. The Negro never gained the measure of relief from the agency’s activities to which his economic privation entitled him. The clause in the basic act prohibiting discrimination was honored far more in the breach than in the observance…

On the other hand, Salmond notes:

To look at the place of the Negro in the CCC purely from the viewpoint of opportunities missed, or ideals compromised, is to neglect much of the positive achievement. The CCC opened up new vistas for most Negro enrollees. Certainly, they remained in the Corps far longer than white youths. As one Negro wrote: “as a job and an experience for a man who has no work, I can heartily recommend it.” In short, the CCC, despite its obvious failures, did fulfill at least some of its obligations toward unemployed American Negro youth.

So where does this leave us? Young black men were not enrolled in the CCC in an honest, direct proportion to their population in the United States, despite language in the legislation that was supposed to prevent discrimination, and once enrolled, blacks were often not treated with the same respect and dignity afforded their white counterparts in other camps and regions of the country. And yet, the occasional incidence of integrated CCC companies presaged by nearly a decade the emergence of integrated units in the military during the latter stages of World War II and eventually the full integration of the military later in Harry Truman’s administration and in time for the Korean War. No doubt, as Bob Audretsch points out in Shaping the Park and Saving the Boys, there is a true need for a detailed scholarly look at African Americans in the CCC, but for now, perhaps we might do well enough to view the issue of race relations as it pertains to the CCC not as a failure, but rather, a small success on the road to larger successes that came later and indeed, successes that continue today.

On the other hand, Salmond notes:

To look at the place of the Negro in the CCC purely from the viewpoint of opportunities missed, or ideals compromised, is to neglect much of the positive achievement. The CCC opened up new vistas for most Negro enrollees. Certainly, they remained in the Corps far longer than white youths. As one Negro wrote: “as a job and an experience for a man who has no work, I can heartily recommend it.” In short, the CCC, despite its obvious failures, did fulfill at least some of its obligations toward unemployed American Negro youth.

So where does this leave us? Young black men were not enrolled in the CCC in an honest, direct proportion to their population in the United States, despite language in the legislation that was supposed to prevent discrimination, and once enrolled, blacks were often not treated with the same respect and dignity afforded their white counterparts in other camps and regions of the country. And yet, the occasional incidence of integrated CCC companies presaged by nearly a decade the emergence of integrated units in the military during the latter stages of World War II and eventually the full integration of the military later in Harry Truman’s administration and in time for the Korean War. No doubt, as Bob Audretsch points out in Shaping the Park and Saving the Boys, there is a true need for a detailed scholarly look at African Americans in the CCC, but for now, perhaps we might do well enough to view the issue of race relations as it pertains to the CCC not as a failure, but rather, a small success on the road to larger successes that came later and indeed, successes that continue today.

Article Copyright, Michael Smith 2011